Dave Buckhout .

Publication Date: November 2010

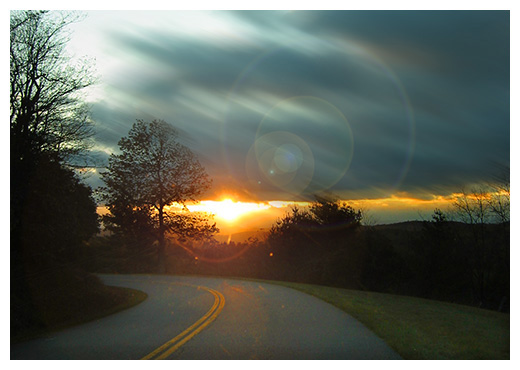

Intro / History | On The Blue Ridge Parkway: October 27, 2008

I am naturally drawn to the mingling of curated landscapes and wilderness lands. The attraction seems instinctive; and considering how familiar the pairing of domesticated nature alongside wild nature has been to our evolutionary journey, the combo has certainly dropped genetic ‘appreciation markers’ in us all. That said, I bring an environmental edge to the table.

I am naturally drawn to the mingling of curated landscapes and wilderness lands. The attraction seems instinctive; and considering how familiar the pairing of domesticated nature alongside wild nature has been to our evolutionary journey, the combo has certainly dropped genetic ‘appreciation markers’ in us all. That said, I bring an environmental edge to the table.

Our yard growing up was my father’s masterwork, a park-like performance every year set within a much larger contiguous run of northern hardwood forest which, at the time, extended several dozen miles through the small Connecticut town where we lived. Add to that mix a unique ingredient: beyond our property and the mentioned stretch of forest, ran Interstate-84 … A well manicured property parked within a wilderness setting, run through by a highway: a personal environmental history that set me up to be instinctively drawn to The Blue Ridge Parkway.

Over the course of many trips over many years, I have been on most of BLRI (The Nat’l Park Service acronym for The Blue Ridge Parkway). Every leg, regardless of length or time of year, has been a rich experience. But one 130-mile leg stands out: October 27, 2008, from Tuggle Gap, Virginia, to Blowing Rock, North Carolina. Atmospheric and seasonal conditions coalesced in a moody dramatic way on that day. That trip would inspire PART 2 of this post.

But first, a history of the roadway and its environment …

It was the success of the partially completed Skyline Drive along a spine of Virginia’s Blue Ridge (in what would become Shenandoah Nat’l Park) that prompted the idea of a much longer, more engineering—and financially—intense extension to the south. The fact that the idea was proposed during the depth of the Great Depression added that much more to the challenge. But the road’s first public sponsor, Virginia Senator Harry Byrd, found a well-timed enthusiastic supporter in FDR. The president had been impressed by a ride down the Skyline Drive. At Roosevelt’s urging, his Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes, approved $4,000,000 on November 24, 1933, to fund the “Park-to-Park Highway” public works program. Four times as long as Skyline Drive and running over / around the highest elevations east of the Mississippi, the “Appalachian Scenic Highway” (its first official title) was designed to link the Shenandoah and the Great Smokies, to be dedicated as national parks in 1935 & 1940, respectively.

The locals in the vicinity of the road’s construction would call it “The Scenic,” and indeed that was the point. Virginia was guaranteed a leg, but the route on the whole was yet to be finalized. A contentious “war between the states” broke out, as Tennessee and North Carolina vied for a lion’s share, if not the whole stretch south of Virginia. The potential boon of tourist dollars for local economies / governments in rural, often hardscrabble communities—no doubt further hurt by the Depression—was evident and led to the fight. But western North Carolina is, if anything, scenic territory; and North Carolina won out. The road would run down The Blue Ridge, veer onto North Carolina’s Black & Craggie Mountains, the Pisgah & Balsam ranges, and end in the Great Smokies. The states would purchase the land, the Feds would build the road.

This was not just a road through the wilderness only; it was meant to mingle the curated and natural, a mix of planned parks, agrarian lands (working & fallow) and wilderness stitched together by the road. The famed landscape architect, Stanley Abbott, would be the man most responsible for the layout of the finished product. Known for overseeing the Westchester County, NY, parkway system (the gold standard of its day), Abbott meticulously designed “a chain of parks and recreation areas, each a destination in itself.” His calculated use of scenic easements was key to acquiring & protecting scenic view-sheds, solidifying their central importance to the roadway. (It is still a signal visitation draw and economic driver; see: BLRI Scenic Experience Project / Synthesis)

This ‘mingling by-design’ would become the central theme of the Parkway, generally. Not only were old farmlands bought and incorporated, the heritage of Appalachian subsistence-farming was put on display. The region’s agrarian, as well as industrial pas—its logging, mining, and milling operations—were highlighted and explained at roadside stops (Mabry Mill in south VA, still amongst the most popular stops); even a never used length of canal along VA’s James River was designed into the mix. This blending of nature and the human imprint, both practical & recreational, created the sense of an outdoor living museum. Cultural history was added to the mix. The locals had long been aware of the Native American legacy. The Cherokee in modern-day North Carolina, the Monacan, Saponi, and Tutelo in modern-day W x SW Virginia, had left remnants of their presence—mainly in the form of arrowheads by the thousands. These tribes were also skilled in land use. Many open fields on parkway land were the result of centuries-old planned burns, farmed fields, and grazed pasture. Further along the timeline: the first forays of Europeans into and across the Appalachians (documented @ VA’s “Explore Park” / NC’s “Boone Trace”), a tide of pioneers and settlers that would flood out the first people. The human story of this environment was brought to life not just in roadside stops & markers, but embedded in the physical landscape itself … And it is this trait that continues to make BLRI a living museum as much for its heritage as for the nature through which the road runs, rangers & historians continuing to fill out the details.

The official project start date was September 11, 1935, ground broken a week later at the VA / NC border. Divided into 45 separate units, progress was slow but steady for the next 6 years. Despite the army of laborers employed under auspices of the WPA, most of the skilled construction work would be accomplished by private contractors. Work-relief teams would put their stamp more on the landscape, creating the ‘park’ alongside the parkway. Intense labor was guided by precision engineering and Abbott’s exacting concept. On June 30, 1936, BLRI became a national park, NPS the manager of the project. Slow and steady, the roadway rolled out in parcels … But then came World War II. Available labor pools, gas rationing, funds reallocation and the focus of the war effort brought the project to a halt. Not quite half-finished, the parkway was a patch of finished lengths (the longest stretch running out about 50-60 miles in either direction from its start point near the state borders), finished stretches of unpaved crushed stone, and many still under construction or ‘proposed’ (which applied to most of the parkway west of Asheville). Efforts to re-start the project post-war were slow to move and met “tight appropriations.” (For an interesting look at the state of the parkway post-war, check out: The 1949 Blue Ridge Parkway Guide Book)

Though already popular, it would take a full decade before a serious commitment to finish BLRI was set-in-motion. As with most cultural commitments, political will follows general cultural trends. And of course, the 1950s popularized the notion of ‘freedom’ embedded in a car-centric society. If not helping lead to “Mission 66″—the ten year plan to finish BLRI by 1966—it certainly colored the cultural landscape in which this re-dedication of efforts took place. A good deal of the visitor-oriented sites now dotting the parkway’s progress were completed during this time. In addition, all but 7.7 miles of the road itself was completed including many of the more challenging engineering-intense stretches (having been halted and left to future construction teams when funds veered toward the war effort in the early 1940s). The most challenging parcel was the final project: The Linn Cove Viaduct. Planned in the ’70s, funded and built in the ’80s, it is unique to the parkway. Most of the road was built into the landscape. The Linn Cove Viaduct wraps around the landscape. Built atop massive stilts, the parkway is elevated above and around the ecologically fragile slope of Grandfather Mountain at this point. It is an engineering marvel. You are literally lifted off terra firma and get the sense you are floating alongside one of the highest peaks east of the Rockies. Officially opened in 1987, the viaduct finally completed the 469 mile BLRI. The Shenandoah and Great Smokies were finally linked.

But the background of the Nat’l Park would not be complete without mention of the diversity of environmental features that lines the road itself. The Southern Appalachians have always been regarded with biological awe. Resting below the furthest extent of the glaciers during the last Ice Age, a wide array of plant & animal species pushed south in advance of the freezing climate, mingling as they did with established flora and fauna native to this region. Those migrants and natives that survived were compressed into a latitude-belt which today includes BLRI. The “wide range of habitats” on and around the mountains themselves adds even more unique environmental opportunities for mass diversity. Once a massive range akin to the youthful Rockies, today it serves as a natural diversity incubator, the NPS website boasting: “climactic variability, a large North-South geographic range, diverse geologic substrate, and many different micro-habitats.” The NPS provides a summary of this already amazing, yet ongoing flora, fauna and landscape inventory. A quick list of the catalog to date: 1400 vascular plants (though biologists feel the actual number is much higher), 400 moss and 2000+ fungi species, 130+ species of tree (as many as are in all of Europe), 70+/- mammals, 50+ fish, 40+/- reptiles and amphibians, respectively (considered “the center of salamander diversity on Earth”) and 250 separate bird species, as well as 100 different types of soil, 600 streams (including 150 headwaters) and an elevation depth of 5700 feet from highest to lowest point, easily supporting both northern and southern species in the process – ALL of this packed into 81,000 acres along a course 469 miles long. It is one of the most biological rich areas on the planet, including many species found nowhere else. (For the complete rundown: NPS BLRI / Nature & Science)

A standard litany of worries shared by most of our Nat’l Parks threatens the natural, scenic and parkway / facility conservation of BLRI: the introduction of invasive species, water & air pollution (the irony of automobile exhaust contributing to that not lost), a warming planet, encroaching development, overuse and chronic underfunding of public lands. But despite these real concerns—useful as impetus for action countering their negative effects—the ability for the parkway experience to amaze is as strong as ever. Case in point: our trip between Tuggle Gap, VA (near Floyd), and Blowing Rock, NC …

A day of unique atmospheric & seasonal conditions – a rapidly moving front (in the wake of heavy rain storms), gusting winds, cool-cold air, peak fall colors—the following is an artistic / literary piece inspired by our trip late that afternoon-evening.

PART 2 » On The Blue Ridge Parkway: October 27, 2008

Easy singing speed bends with the curving lanes, an asphalt ribbon grasping ridgelines tight. Shafts of late-day sun spray white silver over the parkway, as it bounds up from a veiled pocketed hallow. Autumn colors are at peak. Roaring gusts roll up through low mountain gaps. They blast through outstretched canopies. Leaves align parallel to earth with the gusts, scattering in clouds of burnt-ochre flakes. The gusts roll in succession. They power the marching thousands overhead. The procession of low stratocumulus drops distinct shadowfields that liquefy as they hit ground: organic undulating greys atop the lumbering pile of worn hillsides. The hills fade past. Tens of millions of years passing in a single view. The cataclysmic collision of plates that vaulted peaks into the sky has been left to time’s smooth vibe: jutting jagged cliffs dulled to rounded knobs, easy elliptical domes.

Easy singing speed bends with the curving lanes, an asphalt ribbon grasping ridgelines tight. Shafts of late-day sun spray white silver over the parkway, as it bounds up from a veiled pocketed hallow. Autumn colors are at peak. Roaring gusts roll up through low mountain gaps. They blast through outstretched canopies. Leaves align parallel to earth with the gusts, scattering in clouds of burnt-ochre flakes. The gusts roll in succession. They power the marching thousands overhead. The procession of low stratocumulus drops distinct shadowfields that liquefy as they hit ground: organic undulating greys atop the lumbering pile of worn hillsides. The hills fade past. Tens of millions of years passing in a single view. The cataclysmic collision of plates that vaulted peaks into the sky has been left to time’s smooth vibe: jutting jagged cliffs dulled to rounded knobs, easy elliptical domes.

The parkway lopes: sinking valleys, straddling saddles, ramping climbs and descending again. The easy tidal progress repeats this rhythm in a hundred subtle variations: ridge, valley, hillside farm; gap, saddle, creek-riven valley. The patterns conform only to the improvisation of natural force: a million years of rain, a million years of wind, a thousand years of human cultivation.

Split-rail fencing runs the embankment that lines the border of farmlands working and imagined. There is the intersection of museum and real here, collecting and preserving the wild, remote and hardscrabble. The park exhibits agri-heritage, folkways, the one-time outposts of Scots-Irish immigrants transplanted to these roadsides. It celebrates, interprets, recalls a way of life not ancient, but archaic to our present. The Appalachian farmhouse: antique, a hard-scratched clapboard relic settled in a field just beyond split-rail fencing. The motorway museum showcases this fleeting way of life. A fleeting glance turns on the present. Livestock dot rounded hillsides. Lone cattle on ridgecrests set outlines against the mercurial sky. Deep protruding rolls of rock descend into abrupt narrow valleys dissected by creeks. Lands revert upward, quickly: plateaus of rhythmic grassfields. Lively and carefree horses roam these fields. Working fields, working land blends into parkland. The natural real and the natural museum. This blend fuses around a hairpin curve. The scene unfolds a 50 mile deep view. Fifty distinct hills—once ranging angular peaks—slide towards the horizon, looking like the trickling floor of polished stones in a creekbed. Those closest trade mountainside farm and forest. Sprite horses, mellow herds, grassy knolls. Thick russet canopies one valley over. The charcoal cloudscape blankets it all. Gusts howl.

The parkway wraps arches of domed stone. The mountainous roll pours through roaring valleys. Narrow erratic creeks snake black bands through gaps in the humpbacked hills. They speed past. Window views are clouded by bursts of falling leaves riding wild eddies: the charged forthright air. Low late-day light spills over the next rise. It banks angular and hard and cold. It is diffused by lower cumulus. Under-lit, framed in white-gold, the cloud formations march double-time. They leak the white sunlight for an instant here and there, a constant glow that hits the thermometer’s drop. Copse after copse stack up the roadside forest. The poplar, the maple. The dogwood, the elm. The birch, the ash and the resolute oak. They bundle swaths of color, lighting up wooded corridors. Reds run crimson, a ruddy earth-tone. Yellows pool gold glowing and burnt: crisp dark orange tints, gilded. The homespun browns. The tanned hazel. A thousand-and-one shades shower wending lanes. The leaves rain down like confetti. Golden tunnels of forest synch with walls of pine, rhododendron and laurel. Stacked gold, stacked evergreen. The parkway pours through, rhythmic singing speed.

The slate sky is scoured clean by force. Gusting winded energy careens over the convex hills of Appalachia. What did natives think of such wind, such energy, 500 years ago? What did they think of such light, such resolute absolute light? Awe? Respect? Kinship? All three are natural to accept on this day, a day fast turning on night.

The clouds break. A silver cast coats canopies in icy aluminum. Cold rays find obscurity behind the next run of clouds. They trace cloudrims in white electric neon: slow steps toward night. A purple wash dyes an evening tone. It rounds the road’s history set in stone. Deliberate arching curves exhibit the WPA @ work: curved masonry guides the parkway along ledges, hard times put to work boring tunnels through impassable hills, stone-arch bridges. The craftsmanship embeds a sense of permanence in these features. They seem as continual as the sinking hills, the rolling bends, the Appalachians. It fits, as if nature’s intent. Natural whim might not agree; but it takes to the mountains and forests and sliding grassfields as it takes to stone-arch bridges and roadway: with a million years of wind, a million years of rain.

The cloudfield is soft coal, breaking to allow a final rose orange streak of setting sun. It sprays through a keyhole in the wall. Dusk suspends distance under obscurity, mystery. Crisp, cold. A gap view to the north sights successive ranges as they drop rank-by-rank into ghostly silhouettes, charcoal sketches. A clearing of sky ahead, the backdrop of space. A shivering pinpoint of planetary light shines through the cherry-blue dusk.

Sources: Historic American Engineering Record | “Historical Signifigance of BLRI,” by Ian Firth | BLRI Nat’l Park literature | BLRI website