Jim Threlkeld .

Publication Date: 2005

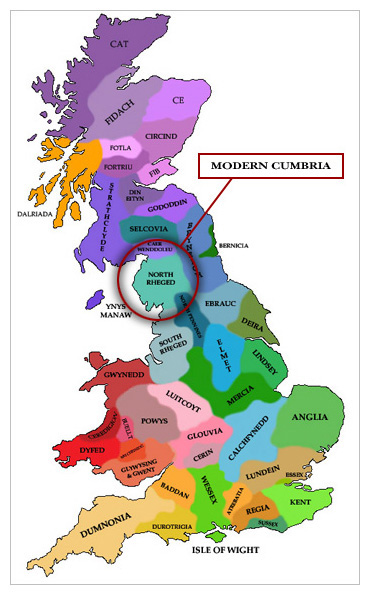

Britain 550 A.D. Map Credit: David Nash Ford, 2003 ©

Britain 550 A.D. Map Credit: David Nash Ford, 2003 ©

When people think of the “Celtic lands,” they usually think of Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany. And while this is not an inaccurate list, there were other Celtic kingdoms in the British Isles that should be remembered.

After the retreat of the Roman Empire, and before the total takeover of “England” by the invading Anglo-Saxon tribes, several Celtic kingdoms flourished, especially in what is now northern England and southern Scotland. There were, among others, Strathclyde (southwestern Scotland), Goddodin (southeastern Scotland), and Elmet (west Yorkshire). However, the most powerful and famous of these was Cumbria (also called Rheged), located in the northwest corner of present day England, roughly equivalent to the modern English county of Cumbria.

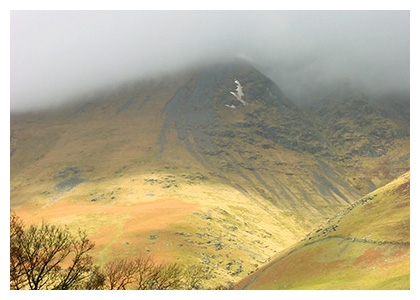

Today the area is famous for its association with the poet William Wordsworth, who was born and lived there, as well as for being home to the Lake District, a dramatic landscape of glacially carved mountains, hills and lakes. The Lake District National Park is in the middle of today’s Cumbria county. The county roughly recreates the outlines of the ancient kingdom, with much the same borders and the capital/county seat at Carlisle. However, 1,450 years have erased much, but not quite all, of the evidence of a very different world.

The Celts began migrating to the British Isles around 500 BC, displacing and/or intermarrying with an aboriginal population that dated back to the stone age. These original native peoples had created many of the great Neolithic monuments, including Stonehenge and Newgrange. In Cumbria they built Castlerigg Stone Circle near Keswick, which, dated at 3,200 BC, is one of the oldest stone circles in Britain. The Celtic tribes lived more or less undisturbed in Britain for roughly 550 years before they were themselves conquered, experiencing firsthand a watershed event in British history: the conquest of the island and its absorption and integration into the Roman Empire.

The Romans were in Britain roughly 55 to 410 AD — about 355 years. In that time the conquered people were Romanized, creating a native British aristocracy that was educated in Roman law, politics, economic organization, the Latin language, and in general the habits of “civilized” living. After the Romans left the island this hybrid Romano-British culture continued, especially in old Roman towns like Bath and Carlisle.

During the Roman occupation the northern region of Britain was governed by proxy kings, or Duces Brittannairum, who pledged allegiance to Rome. These kings were the descendants of the original Celtic rulers in the region and so commanded the loyalty of the local tribe, the Brigantes. The last of these proxy kings, and one whose rule seems to have straddled the transition from Roman to native authority, was Coel Hen (Cole “The Old”), who lived c. 350-420. He is “Old King Cole” of the nursery rhyme. His kingdom of Northern Britain covered the area of the island north of modern Liverpool up to Hadrian’s Wall (nearly to modern Scotland) and spanned from coast to coast. The kingdom of Northern Britain was split over the years among Coel’s descendants, creating a patchwork of increasingly smaller kingdoms.

Ravenglass, South Cumbria & The Irish Sea at Sunset

This jumble of northern kingdoms bickered and fought each other for a hundred and fifty years or so. Rheged /Cumbria emerged as the region’s most powerful kingdom under its ruler King Urien (ca. 530-590), a descendant of Coel Hen. He made his court at Carlisle, the old Roman city situated near Hadrian’s Wall, where the memory of Rome still lived in architecture, engineering, Latin literature, arts and learning. The city would still have had Roman buildings, aqueducts, baths, manuscripts, streets, and defensive walls, plus a Romanized ruling elite, creating a culture that does not easily conform to our modern preconceptions of “barbarians”.

Urien attracted the “best and the brightest” to his court, including the famous Welsh bard Taliesin, whose songs in praise of the king as a wise, learned, and benevolent ruler became famous in their day, and spread his legend. Composed in the mid to late 500s, they are some of the oldest poems in Welsh literature:

More is the gaiety and more is the glory

That Urien and his heirs are for riches renowned,

And he is the chieftain, the paramount ruler,

The far-flung refuge, first of fighters found.

Rheged’s defender, famed lord, your land’s anchor,

All that is told of you has my acclaim.

Intense is your spear-play, when you hear ploy of battle,

When to battle you first come ‘tis a killing you can…

The Angles (Anglo-Saxons) are succorless around the fierce king…

Gaiety clothes him, the ribald ruler,

Gaiety clothes him and riches abounding,

Gold king of the Northland and of kings, king.

Evidence suggests that Urien did indeed rule wisely, and his kingdom prospered under his leadership.

Seaside at St. Bee’s & A Public Footpath to Whitehaven

Taliesin spoke and composed in Welsh, but he could have been easily understood in Cumbria, where the language spoken was Old Cumbrian. Old Cumbrian and Old Welsh were related languages (or dialects, depending on how much they’d diverged). Both belong to the Brythonic Celtic language family (Irish and Scottish Gaelic are Goidelic, the other branch). Vestiges of Old Cumbrian remain in the dialect of modern Cumbria down to the present: for instance, the numbers used for counting sheep today are dialect variants of their Old Welsh counterparts: yan, tan, tether, mether, pimp, sethera, lethera, hovera, dovera, dick (1-10). Place names like Penrith and Blencathra are also Brythonic linguistic vestiges (Blencathra, a mountain in the Lake District, means “Devil’s Peak” in Old Cumbrian, so called because it was thought that the Celtic god of the underworld lived there). The place names Cumbria and Cumberland actually refer to the Brythonic people. “Cymri” or “Cumber” means the Brothers or Companions – it was what the Welsh peoples called themselves (“Welsh” is actually the Anglo-Saxon word for foreigner). So Cumberland is literally “land of the Cumber.” The name Rheged seems to derive from the Brigantes, the name of the original Celtic tribe that populated northern Britain: Brigant became Breged, then Rheged. This name is found in the modern place name Dunragit – Dun Rheged (fort of Rheged), a hill fort ruin in the northwest.

It should be remembered that, in spite of the “civilizing” influences of Rome, Urien was still a warrior-king, and British culture was still very much a warrior culture, centered around the skills and ferocity of its mounted fighters. Horses were central to this way of life, and the horse was sacred to the Celts. This is reflected in their mythology and crafts. From the horse goddess, Epona, to Gray Sea, the magical horse of the Irish hero Cuchulain, horses are woven all through Celtic legend and art, figuring prominently in their designs for weapons and jewelry. It’s easy to see that the horse was vital for the maintenance and prosperity of these tribal kingdoms, as cavalry mounts, status symbols, and, just as importantly, as pullers of plows and carts.

A living remnant of this equine tradition can still be found all around modern Cumbria: the Fell Ponies, who wander freely on the hills of the Lake District, are descended from the native mountain ponies and the horses of the Roman cavalry that were stationed along Hadrian’s Wall. These small, dark, sturdy horses are ideal for the rugged terrain of the north country. The warriors of Rheged would have had this hardy hybrid to ride into battle. They may also have had the cultural memory of their ancestor’s service in the Roman cavalry, including knowledge of military organization and fighting techniques. This combination may have contributed to the kingdom’s dominance of its neighbors. Interestingly, the territory of the modern day Fell Ponies corresponds almost exactly to the old kingdom of Rheged, as if the ponies were shells deposited there by a sea that has long since dried up. Like the Old Cumbrian place names that dot the landscape, they are relics of a vanished culture.

The Harbor of Whitehaven, North Cumbria & Cumbria, South of the Lake District

Because of his stature among the northern kings, Urien managed to stop the Welsh peoples from fighting each other and united them to fight their common enemy: the Anglo-Saxon raiders who were establishing themselves along the eastern coast, savage fighters who were slowly conquering the island. The Anglo-Saxons were pagans, worshipping bloodthirsty gods that demanded human sacrifice. This would have been a horrifying encounter for the Cumbrians, who not only were a bit more civilized, but were Christians as well. They had been converted by Irish monks doing missionary work in northern Britain in the late-400s, sometime after St. Patrick’s mission to Ireland. In the Christian religion of the Cumbrians was yet another echo of Rome.

Urien led the allied assault against the “English” and drove them back to the sea, dealing them a major defeat. But before the victors could take advantage of this, Urien was murdered, assassinated by his jealous ally, King Morcant of Din Eiden (an old kingdom centered around present day Edinburgh). Morcant wasn’t pleased that Urien got all the credit for the victories against the invading tribes, and sought by his murder to become the leader of the Welsh alliance. But the murder only sowed distrust and disunion, and the Anglo-Saxons were able to come back stronger than ever.

Urien’s son Owain took over the kingdom, and though he was a fierce fighter and a good king, he died after only a few years. Owain was succeeded by his youngest brother Rhun, who was in turn succeeded by his son Rhoedd, probably the last king of an independent Cumbria. By the 630s Rheged was absorbed into the (now) powerful Saxon kingdom of Northumbria, probably through the marriage of Rhoedd’s daughter (and Urien’s great-granddaughter) Riemmelth to the Northumbrian King Oswy. Their son, Alcfrith, became king of Northumbria after his father’s death. After nearly 200 years, the Celtic kingdom of Cumbria ceased to be.

An interesting side-note: Owain’s illegitimate son was St. Kentigern, also known as St. Mungo, the patron Saint of Glasgow. This son was the result of an illicit relationship between Owain and Princess Taniu of Goddodin, a Brythonic kingdom in present day Scotland.

The murder of Urien was one of the turning points of British history, though it is largely forgotten today. It is the tragedy of the Celtic kingdoms of the north: because of the treachery leading to his assassination, the confederation he created to fight the Saxon invaders collapsed, insuring the end of all the Brythonic kingdoms and the triumph of the Germanic invaders. Had they held together and fought on united, the map of modern Britain might have looked quite different, with a much larger Wales extending along the western coast up to the Solway Firth at the Scottish border. However, as things turned out, the story of Rheged is an obscure and forgotten corner of history.

Ruins of a Roman Bathhouse & The Village of Threlkeld

However, it isn’t just the dry history that appeals to me when I read about Cumbria. The rugged landscape of the North, with its misty mountains and moors traversed by mounted warriors doing battle, is a mythic landscape, and appeals to my love of medieval legends. Mythic, legendary, heroic – all of these terms accurately describe the stories of Cumbria. There is, however, another, equally applicable term (and one of special interest to me): “Tolkienesque.”

Let me explain: from 8th grade through my senior year in high school I read The Lord of the Rings annually. As I got older I became increasingly interested in the sources of Tolkien’s fictional creation. I discovered that, as befitted a learned Oxford don, he’d used elements of Anglo-Saxon, Norse, Finnish and Celtic cultures, blending and shaping the various myths, legends and languages. In Cumbria I feel I’ve discovered one of the real worlds from which Tolkien’s Middle Earth was created.

In fact, I associate the kingdom of Rheged and King Urien with the kingdom of Rohan and its ruler King Theoden, from The Lord of the Rings. Both societies are tribal kingships based around a culture of horse-riding warriors. Both have been influenced by a society of greater cultural, military and technological sophistication: for the people of Rheged it was the Empire of the Romans, for Rohan, the Kingdom of Gondor. Urien’s court at Carlisle may have been similar in some ways to Theoden’s Hall, although, with its Roman heritage, it was probably more sophisticated. Taliesin, the bard of Urien’s court, a druidic seer and wise man, is a figure akin to the wizard Gandalf. In light of these ideas, it’s worth noting that Tolkien claimed to have found the legends of Middle Earth in an ancient manuscript he called The Red Book of Westmarch. In fact, many of Taliesin’s songs to Urien are contained in a medieval Welsh manuscript known as The Red Book of Hergest. Considering that Tolkien based the Elvish language Sindarin on Welsh, it’s certain that he know of this manuscript, as well as the legends of Urien.

The mythic potential of the Cumbrian royal house did not go unnoticed by later writers. The medieval composers of the Arthurian romances incorporated both Urien and Owain into their stories. Urien was supposed to have been married to Arthur’s half-sister, Morgan le Fay, while Owain was a knight of the Round Table and had several stories of chivalrous adventures attributed to him. Over time the entire region came to have associations with Arthurian legend. For instance, Carlisle has been put forward by some scholars as the location of a northern Camelot. The action of the late 14th century poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is thought by some scholars to have taken place in the forest of Inglewood, not far from Carlisle. And in some of the tales King Arthur and his knights are reputed to have ridden black horses. Some writers believe that this refers to the Fell Ponies, which are usually black or dark brown.

Even after becoming a part of the English kingdom of Northumbria in the early to mid 600s, Cumbria continued to be a culturally autonomous region. The harsh and inaccessible terrain and different language made for continued isolation and emphasis on traditional ways, not unlike the Kurds in modern Iraq. Evidence of this Cumbrian cultural continuity can be seen in the legend of King Dunmail, a tale set over 300 years after the conquest of Cumbria by the Northumbrians.

King Dunmail was said to have been the last king of Cumberland. Perhaps, like the proxy kings of Roman Britain, he pledged fealty to the English while ruling a culturally autonomous region. The story goes that in 945 King Edmund of England and King Malcolm of Scotland joined forces and defeated King Dunmail at a battle on the border of the counties of Cumberland and Westmorland, in the middle of the old kingdom of Cumbria. A pile of rocks was erected over the spot the king was said to have fallen. This cairn, known as Dunmail Raise, can be seen today beside the road running between Keswick and Grasmere. Legend has it that the crown of the kings of Cumberland was thrown by the king’s sons into Grizedale Tarn, a nearby lake, so that the victors could not flaunt it as war booty. The king’s sons were also said to have been later caught by Edmund, then blinded and castrated, bringing the royal line of Old Coel and King Urien to a final end.

William Wordsworth, who was born and raised in the Lake District, and lived in Grasmere, referred to this event in his poem “The Waggoner” (1819):

The horses cautiously pursue

Their way, without mishap or fault;

And now have reached that pile of stones

Heaped over brave King Dunmail’s bones;

His who had once supreme command,

Last king of rocky Cumberland;

His bones, and those of all his power

Slain here in a disastrous hour!

Fog on a Fell & Lake Bassenthwaite, Lake District

King Dunmial may have been a Celtic king, but he would have had many Norse soldiers in his army. The Norse began migrating to the area in the early 900s, second and third generation settlers from Ireland and the Isle of Man, who came to Cumbria not to raid but to settle. They were the surplus population of a Norse maritime empire based in Dublin, a Viking city that functioned as the Venice of the Irish Sea, with outpost at other Irish port cities like Limerick and Cork, as well as at York in England. Many Lakeland terms come from Old Norse: tarn (small lake), dale (valley), fell (hill), beck (stream), and keld (spring).

With Dunmail’s defeat and death in 945, the last vestige of the Celtic kingdom of Rheged, with its links to the island’s pre-Anglo-Saxon past, disappeared. That history, stretching from the great Romano-British kingdom of Northern Britain and its founder Coel Hen, to the triumph and betrayal of King Urien of Rheged, came to a bloody end with the defeat of Dunmail on the lonely fells of Cumbria.

Or did it? Maybe the story isn’t over quite yet. The legend of Dunmail has an Arthurian parallel, stating that one day the last king of Cumberland will rise again, taking his crown from Grizedale Tarn and returning to aid his people. Well – we’ll see. It hasn’t happened yet. In the meantime, however, modern Cumbria is a living reminder of this forgotten Celtic kingdom.