This is one of those rare pieces that, for us, becomes more treasured as it ages. It is a true time capsule. Originally published in 2002—hence going online prior to the 2004 ALCS miracle and World Series victory that would change everything for Boston Red Sox fans—this piece documents an impromptu heritage tour taken / Sox game taken-in: August 2002. There is no way to mask its age: knuckleballer Tim Wakefield still on the mound in mid-career, the one forgotten year that Rickey Henderson played for the Sox late in his illustrious career, the Green Monster in its original form with only nets (not seating) hanging over Landsdowne, and of course: all the amazing early-millennium success still nothing more than the fevered dreams of long-starved Boston fans. But despite the time-stamp—or perhaps because of it—the timelessness of the experience of going to the “friendly confines” shines bright. History wraps around the present in a way much more obvious than usual @ Fenway. Years fall away with ease. (Of course, all such nostalgia was made much easier to digest in that the Sox finally did win it all!) Still, to read through this piece so long after its original publication puts the continuity of this complex—still very much an active sports / culture history-maker—on full display. And so, here is a blast from the Almanack past doing its best to render age irrelevant.

Dave Buckhout .

Original Publication Date: September 30, 2002

Introduction .

Some days I wonder why my Dad didn’t raise me as a Yankees fan. The reason is actually due to chance. My family tree follows its deepest roots to New York City and the modern generations were all Yankees fans. But in 1959, a full decade before my arrival on the scene, chance interceded. My Dad got himself a job in East Hartford, Connecticut. To that point most of my family’s branch of the Buckhout tree had viewed New Jersey and Long Island as being far from home. Dad it would seem was a pioneer, far, far from the Big Apple. The distance was actually negligible. But it was far enough from the "City" to deny my Dad the Yankees’ regular broadcast. It was, however, within dubious range of Boston. So, loving baseball, as much for its uncomplicated background noise during the unwinding of long summer workdays, as anything, the Red Sox became my Dad’s team and the household’s team of choice (much to Mom’s chagrin, tradition apparently running a tad deeper on my maternal side) . . . Given the strict rulings on the rivalry of Red Sox v. Yankees, from a legal sense it is actually a capital crime to defect from one club’s faithful to the other, the penalty for violating the statute, it’s been rumored, consisting of equal parts unmitigated scorn and sure banishment to the deepest depths of hell. But, what the hell, Dad could only tune in the Red Sox. And from a consumer standpoint, he had to work with what was available . . . So, thanks to the now ancient limitations of the television antennae, I was raised a Red Sox fan and grew up with Luis Tiant, Mike Torrez, Fred Lynn, Dwight Evans, Jim Rice, Rick Burleson, Jerry Remy, Butch Hobson, Carlton Fisk and, of course, Yaz — Carl Yastremski. I was young, but knew that Fisk’s homer was a once-in-a-lifetime show during Game 6 of the 1975 World Series. I was plenty old enough to know what Bucky Dent’s homerun meant in the 1978 playoff game. And we don’t even need to tread on the often told tale of Buckner’s error in game 6 of the 1986 series, which has become cemented into the public’s imagination as the very definition of the Red Sox experience (I personally blame the bullpen — it wasn’t poor hobbling Bill that set up that debacle). I prefer, as do most Red Sox fans, to remember Dave (Hendu!) Henderson’s ninth-inning homer in Game 5 of that year’s ALCS, with the Angels a strike away from the World Series. That homer was much more than the tired beaten hungry Red Sox faithful would have dared hope for, wrestling destiny from California (and implementing the beginning of a tragic end to Angel’s pitcher Donnie Moore’s career), the BoSox winning Game 5 in extra innings before coming back to Fenway and finishing off the Angels in Games 6 & 7 . . . The ‘80s, the era that I remember best. It delivered Wade Boggs and Roger Clemens to the "friendly confines." Sure, both would eventually defect to the Yankees, what with all their shiny pretentious championship rings and fat war chests of television revenue . . . But stopping myself, lest I grow bitter, those three or four games a year that we’d make the hour and a half trek to Boston’s magical Fenway Park during the 1970s & ‘80s rank right up there among the defining moments of my growing up. The Sox didn’t always win. But it really didn’t seem to matter much. We were at Fenway.

* * *

Can a baseball stadium be considered a heritage tourist destination? Not most. The majority see the wrecking ball long before the term "classic." Fenway Park is one of the very few exceptions. One stroll around the park steps you back in time to an era when all ballyards were crammed into such odd angular lots within existing roads and old neighborhoods hovering on the fringe of the downtown. They were all like Fenway once. Heritage, history? Excepting Chicago’s Wrigley Field, Green Bay’s Lambeau and, yes, Yankee Stadium, there is no more a historical sports setting in the country. If you’re a baseball fan, Fenway’s a cathedral. Last August, I made it back to Fenway. It was a beautiful night, on the chilly side. Oakland was in town and the two teams were then battling for the wild card slot in the AL playoffs. Kerri & I stayed at the old Buckminster Hotel up on Beacon Street, a favorite for Sox fans in from out of town. From there, it was only a few hundred yards down Brookline Avenue and over the I-90 bridge to the park. We arrived early. Still, arriving at four p.m. seemed late. The bars were filling up, vendors were selling "Red Sox souvenie’ahs, he’ah" and the whole block smelled of grilled links. We had arrived . . . Walking up on the park presents no great shakes. It actually looks a bit run-down. But then, there’s its charm. When talk started a few years back of tearing it down and building a new Fenway a few blocks over, there were two camps: those who were outraged and those who viewed it as inevitable. However you felt, though, no one liked the idea of losing the old park. The latest talk is that of a massive renovation. Personally, luxury boxes and gourmet vending don’t make the stadium. Baseball is about the simple things. The ticket-holder will find all modern conveniences crammed uncomfortably and unnaturally into Fenway Park, a reminder that we as a society, and especially those who play and run baseball, are much better off than those who came to cheer on the game seventy-eighty-ninety years ago . . . It has seen eras, this old ballyard. It’s even seen four world championships: 1912, 1915, 1916 and 1918. Ah, to have been a Red Sox fan in the ‘teens.

Signage @ Brookline / Yawkey & Close-Up of the Brickwork of Fenway

2002 was the ninetieth season of baseball at Fenway and the anniversary was in full swing. We turned down onto Yawkey Way and came up on my favorite fact about the park etched into a plaque hung on the stadium’s front. It commemorates the opening of Fenway Park on April 20, 1912 — the same week the Titanic sunk. Where Brookline meets Yawkey Way behind the third-base grandstands is the great pre-game gathering spot. There are gates located all around the park, but here is where community and baseball are one. On that late-afternoon, the sense of community and neighborhood prevailed. Few things say community more succinctly than a row of successful small businesses. Whether pedestrian or fan, purchasing team colors or a bottle of water for the walk to the "T," those out and about took full advantage of the business district around the park. People on their way to the game mingled anonymously with those catching a bus or going out to dinner. Students were headed towards Boston University just across Beacon from the Buckminster. It all said big city, everyone going about their business as individuals within the whole. This in its own right was one of the tightest links to the past that Fenway offered us that night. The planning and implementation of traffic flow and crowd control drives all modern stadium constructions into a self-contained sphere that is pretty well removed from the city that the team represents. But that wasn’t the case when they built this park on what was once the swampy "fens" behind Boston’s Back Bay. This field is as much a part of the city’s character as its colleges, commons, revolutionary heritage and its lack of the letter "r." We walked the length of Yawkey, were sold on a vendor’s recommendation that his stand sold the best "saw’sages" — "the best," he assured me. The added onions and peppers helped clinch it. It was pretty well-timed, too, as we were only working on a quick breakfast and airline peanuts to that point in the day. The selection of hats and apparel from the souvenir shops along the way was overwhelming. So we stuck to functionality in anticipating a cool evening and bought two long-sleeved shirts — well okay, and a hat. Only the resolute can resist the sharp wit and salesmanship of the experienced Fenway hawker.

After we agreed to meet back at the plaque in forty-five minutes, I set off for a stroll around the outside of the park. It would only take me thirty minutes, including a number of stops for notes and photo-ops . . . At a capacity of just over 34,000, Fenway is by far the smallest major league baseball stadium. Back in the day before fire codes, owners would pack this place with as many bodies as wished to buy a ticket — the record crowd at Fenway being up near 45,000. But with the advent of intelligent crowd-management after WW II and the abolishment of standing-room-sales, tickets were sold based on available seating only. Still, the minuscule by-today’s-standard size of the park was once a pretty standard capacity — Brooklyn’s "palatial" Ebbetts Field only held 25,000. Today, Fenway is dwarfed by the 50,000 seat standard of most MLB parks. But like many things that withstand the test of time, the general character of the old baseball stadium is again "in." The nostalgic features of irregular fencelines (a result of parks often shoehorned into less than square lots), close-to-the-action stands and unique architecture are again the defining elements of the baseball stadium. Gone, and not a moment too soon, are the days of the multi-use circular unimaginative behemoths of the 1960s & ‘70s lined of astro-turf and cheap seats that weren’t even in the same zip code as the playing field. Sure, the case is easily made that many baseball owners have recently held their cities hostage with demands for shining new luxurious and expensive parks subsidized by the respective cities through resident property taxes. But I can see it another way, in that most of the cities that couldn’t produce enough civic pride to alter the financial and municipal reasons that demolished their old parks are now confronting that regret by attempting to recreate the past. Not every resident of a city cares one way or another about their hometown baseball team. Nevertheless, a stadium is a representation of civic character — and Fenway is a feather in Boston’s cap, this simple stolid surprisingly ordinary little place making the case for historic preservation all by its self. Civic planning and development in Boston has a notorious reputation for big-time botches. But investing the city’s character into the future of Fenway Park, thereby saving it from the wrecking ball, has created heritage where other cities simply look to create revenue. I guess I just find it ironic that old is "in" again, because when you’re at Fenway it’s neither old or new, it’s just another season of baseball.

T.V. Vans on Ipswich & Landsdowne Behind the “Green Monster”

I made my way down Van Ness Street and past the player’s parking lot. Stuffed to the gills with over-sized gold-trimmed SUVs and a fleet of sleek luxury sedans, it made the labor negotiations that were raging miserably at the time seem flat out ridiculous: millionaires arguing with multi-millionaires over millions, a situation that those of us who love baseball for the game itself found hard to stomach (both sides would read the writing on the wall and avert a strike, for once). I banked onto Ipswich Street and walked along behind right-field. When Fenway was built radio was still experimental. Needless to say, there are precious few accommodations for modern-day television crews. It was obvious as I walked past remote broadcast vans parked up on the curb as if only to unload vending supplies and be on their way. Their satellite dishes trained for the sky, miles of cord snaked up from the vans and laid draped over fences and the outer walls of the bleachers as in hasty preparation for a late-breaking story. But again, it’s another example that the modern-era has adapted to the quirks of this old field, the preservation of Fenway just a subconscious understanding.

Landsdowne Street / Boston Skyline & Yawkey Way Main Entrance

I walked on around the outfield bleachers and turned onto famed Landsdowne Street, which now shares its name with the greatest player in Red Sox history: the "splendid splinter," Ted Williams . . . Ted, having passed on earlier that summer, was memorialized for the remainder of the 2002 season, his No. 9 cut into the left-field grass where he played . . . Out along Landsdowne, the crowd was filling in. Buses passed from the outer reaches of New England, a charter pulling in from New Hampshire and then one from Vermont — this being New England’s team and all. The laboring sounds of the buses melded with the rattling bass of hip-hop quaking from a passing car and the milling sounds of the crowd: people waving, yelling and gathering on the sidewalk in front of Gate C beneath the park’s outfield messageboard. I continued on up Landsdowne. The park’s exterior along this stretch could be the outer walls of a mill or a meat-packing plant. It is that plain, giving no indication of the building’s purpose. I soon came out underneath the netting atop the most recognizable landmark in baseball: the "Green Monster." A 37 foot-high target for hitters and a nightmare for pitchers, the wall, which lines left-field, is the most unique feature of an entirely unique field. Necessity made the Monster. Landsdowne angles westward to where it connects with Brookline and drops the available acreage to a scant 315 feet at the left-field foul-pole. Back in 1912, city planners were less likely to move a street to accommodate a ballfield, even for the pros. And since 315 feet from homeplate is a chip-shot for a major league hitter, even ninety-years ago, so was born the added height of the "Green Monster." Since its addition, the wall has nurtured a character all its own, awarding singles on what would be a routine pop-up in another park, yet awarding only a single on what could easily be a double or triple in another park. Even with the additional height, homeruns drop fast and furious over top of the Monster. You learn to love and hate it during a game, the mood depending on whose triple gets choked into a single or whose homerun sails into its netting. I remember watching Dave Kingman, then with Oakland, hit mammoth homeruns clear over the netting during consecutive years at Fenway in the early ‘80s. The "Green Monster" was not to blame on those nights. No park in the universe could have held those shots. I could tell my stroll around Fenway’s friendly confines was almost complete, as the sound of "programs, get yah’ programs" echoed from around the corner. I soon met back up with Kerri amidst a Yawkey Way then swirling with eddies of fans hitting up the vending and heading for the now open gates. Anticipation was in the air, as it always is when the Red Sox remain in the playoff race this late into a season. The hope that each spring instills in the Boston faithful was still burning hot on that Tuesday evening last August, despite the near predictable heartbreak that August and September always seem to produce. As if to prove the loyalty of the legions then lining up at the turnstiles, a billboard ad for a jewelry store at the corner of Brookline and Yawkey proudly proclaimed, "83 years without a ring and still married."

* * *

Our seats were located in the right-field box and were not bad, considering that the right-field grandstands are notorious as the worst seats in the house. Regardless of the quality of the view, they were full — as was the entire park. That I’d been able to land such good seats was a stroke of luck I’d been reveling in since I purchased the tickets back in early June . . . The usher showed us to row FF and gave a quick wipe of seats 1 & 2 before we sat down. He’d likely done this tens of thousands of times, but it seemed like personalized service to us. "Enjoy the game," he said. We took our place amongst the brimming faithful, situated about ten rows into the box from the right-field foul-pole: known here as "Pesky’s Pole." In one of the many odd playing field angles, right-field curves sharply from 380’ down to a mere 302’ at the foul-pole. Famed 1940s Red Sox shortstop, Johnny Pesky, once curved a comically short line-drive homerun around the pole, a hit that would have been a routine foulball in every other outfield in the league. Red Sox pitcher Mel Parnell witnessed the homer and coined the phrase, which stuck despite Pesky’s notable lack of power (that was, in fact, 1 of only 6 homeruns he hit during his entire Fenway career) . . . So, with a decent view, a beer and popcorn in hand, we settled in behind Johnny Pesky’s dubious memorial. A blinding sun perched over the third-base roof seats, but the coming of a cool evening was evident. The history of the park and heritage of this team was settling in as routine by this time — I mean, even the foul-pole had a story to tell. As if we needed additional validation, Luis Tiant, the animated and beloved hero of the 1970s Red Sox pitching staff, threw out the first ball to his battery-mate, hall-of-fame catcher and New England native Carlton Fisk. It was Fenway. It was game time.

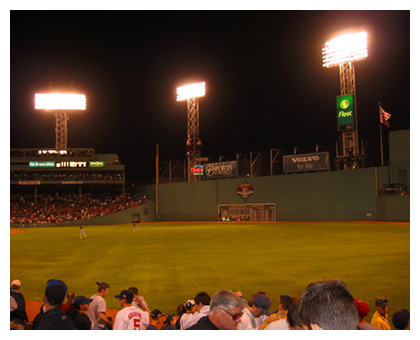

Right-Field Grandstands & Outfield Grandstands

The pitching match-up was Boston’s Tim Wakefield, veteran of the lost art of the "knuckleball," and a rising star, A’s pitcher Mark Mulder. The top of the first breezed by without incident and the Sox came to bat in the bottom half of the inning. Mulder’s first-pitch buzzed past the senior "gamer" of the game, Rickey Henderson. Knowing that Mulder is much younger than I am and that I grew up watching Rickey Henderson (in fact, it was Henderson’s A’s that knocked out the Sox in the 1988 ALCS), I realized that Mulder grew up watching Rickey swipe bases and taunt the opposing team’s crowds just like I had. And there they were, squaring off. The kid got the better of the veteran this time on his way to retiring the side.

The second inning was uneventful. Wakefield cruised through an easy top of the third. The most action was in the aisles, as vendors in yellow shirts buzzed like bees up and down every section in the place: bottled water, sodas, beer, ice cream sandwiches, cotton candy, popcorn, peanuts, cracker jack and the venerable Fenway Frank. I had two. Manny Ramirez soon strode to the plate. The sight of the Sox slugger moved the crowd into chanting, yelling, urging, funneling the collective energy of 34,000 into the head of the bat and believing that this would surely produce results. But Ramirez popped out to a swoon. It seemed we were headed for a pitcher’s duel.

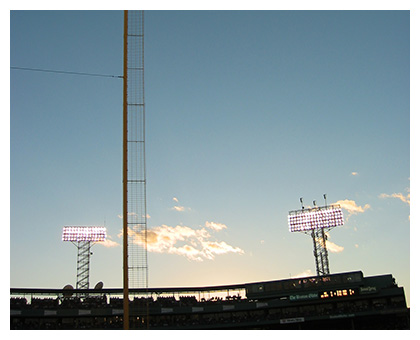

View from the Right-Field Grandstands & “Pesky’s Pole” at Twilight

Wakefield gave up his first hit in the top of the fourth, but that was all. The Sox plated the first run of the game in their half of the fourth. Two quick outs followed with a runner still in scoring position. Henderson came up for another tour at bat, the crowd sensing opportunity. As he has done more than any player in MLB history, Rickey drew the walk. The crowd began to leak anticipation, a swelling roar that filled the place. The next batter, Trot Nixon, was hit by a pitch, the crowd venting an angry vocal demand for the pitcher’s head. But our wish for medieval-style revenge was transplanted into a fist-shaking call for payback, as Nomar Garciaparra — possibly the most beloved modern-day sports star in sports-rabid New England — stepped up to plate, the bases full of Red Sox. Individual cheers and jeers and yells swelled into a deep roar that lit up the old park like an electric spike. Surely, the intimidation alone would plate two, maybe three runners. But it was for naught as Nomar flied out. Still, we were on the board: 1-0 Red Sox. Whole swaths of sections disappeared down the tunnels, heading for the concessions and the bathrooms, while those left in the stands dropped into conversations, hundreds of easy discussions resonant in reverberating off the old beams of the grandstands.

Having traveled over a thousand miles to see the game, Kerri & I, feeling we had a bit more at stake than most of our fellow Sox fans, felt convinced that we were on the road to victory. Well, that dream began to falter in the fifth. Wakefield put two A’s on and then served up a meatball. With the ominous crack of bat hitting ball, a great singular groan escaped the crowd and accompanied the ball’s trajectory as it arched into the netting above the Green Monster. It seemed like 34,000 fans had suddenly stubbed their toes, a united reaction half-pain, half-annoyance. Just like that, it was 3-1 A’s.

In the top of the sixth, things took a turn for the ugly as another ball made high-arching tracks for the Monster’s netting. It was 5-1 A’s, and the Fenway faithful began to look unfavorably on their big green wall in left-field . . . Well, you can probably see where this is going. Yes, the Red Sox wound up getting killed that night. Few things, for Red Sox fans, stand out past the sixth inning. The bottom of the seventh was welcomed with a defiant, "let’s go Red Sox! clap-clap clap-clap-clap, let’s go Red Sox! clap-clap clap-clap-clap." The chant lost momentum with each successive out, until the third finally snuffed out all optimism. Still, the chanting, the real hope in the face of long odds, had showed a slice of your standard "beantown" defiance . . . Having known and been around Boston my whole life, it really is no wonder to me that the Revolution started here . . . All civility was soon lost as hopeful chants and cheers degenerated into choruses of boos and hazing as the bullpen came apart in the final innings. Having paid the ticket and having poured devotion onto our ballyard warriors for seven innings, with no results, the instinct to cull some satisfaction out of the evening came pouring out, negatively. I liken it to a theatre full of unfulfilled patrons, tossing ripe tomatoes and melons at the failure on stage. "You suck," was the common theme. With the end of the eighth, and the score 9-1, the faithful left in droves.

We stuck it out to the last painful out, had no bus to catch, no long drive home. We could see the top floors of the Buckminster striving along the skyline beyond the Green Monster, our journey home that night but a few hundred yards. So we stuck it out, stuck it out in the great jading Red Sox tradition: masochistic, some have — aptly — called it. But as much for fatalism and self-pity, we stayed simply because we wanted to. We weren’t there for the misery that had unfolded on that cool August night, but for the setting despite the loss. We were there for Fenway Park as much as we were there for the Red Sox . . . Walking around that evening, the surrounding streets and avenues, mingling with the anticipant crowds, buying "souvenie’ahs" and depleting our bank account, eating "saw’sages" and incrementally raising our cholesterol, entering into the magical confines, taking our seat, ordering steamed Fenway Franks, the scene, the fans, the setting — it may sound like the "loser’s" consolation, but Fenway was victory enough for us that night.

Old-School Concessions Beneath Grandstands & The “Monster” at Game’s End

So, that was our night at the old ballyard last August. In finishing let me say that I believe the heart and soul of heritage is as much about the present as it is about the past, which reverts me to the question I asked myself earlier . . . Can a baseball stadium be considered a heritage tourist destination? . . . Not most. But then there’s Fenway Park in Boston, Massachusetts.

End Note: I can’t believe that I forgot to mention the hand-operated scoreboard embedded into the "Green Monster" — a high crime for which I am hanging my head. Forgive me, Fenway.