Dave Buckhout .

Publication Date: September 2010

Part 1: Dedication | Part 2: Knoxville, Summer 1915

Introduction ›

Aside from the lit-set, classic film buff crowd and anyone who has taken a college-level English course over the past 30-40 years, James Agee is all but unknown. In his own lifetime he was accepted and ignored, revered and reviled, while still maintaining a good deal of anonymity. Full well-done bios are a quick search away, so I’ll rip through the life and art-shaping high points: born middle class, Knoxville, TN, 1909 … father tragically killed in car wreck at age 6 … enrolled in Episcopal boarding school, forms lifelong friendship with Father Flye (father-figure, absentee therapist, his one tenuous yet constant tether to God) … attends renowned Exeter prep school in NH … on to Harvard, edits campus literary journal, graduates … becomes a journalist, becomes un-enthused, transitions to overtly enthused and freeform film critic … despite limited free-time, manages to create a mountain of wildly improvised AND highly disciplined poetry, verse, fiction, non-fiction … oh, right: and is a risible self-destructive barfly / insomniac who drinks and smokes his way to the heart attack that kills him in the backseat of a NYC taxi: May 16, 1955. Agee is dead by the unacceptably young age of 45.

In his day, he was probably best known as film critic for Time and more visibly The Nation during the 1940s. (Library of America published over 500 pgs of reviews in its Agee, Film Criticism and Selected Journalism; entertaining reading, though you have never heard of most of the films.) Posthumously, Agee is better known for a work of fiction and non-fiction … A Death in the Family was an unfinished manuscript fictionalizing the death of his father and the immediate moments and days afterward. It is stunning, incisive, lyrical and ultimately heart-rending. Despite missing Agee’s finishing touches, it was admirably pieced together by friends / editors and published. It won the Pulitzer in 1958 … But it is the work of non-fiction for which Agee is arguably most famous (or infamous, depending on the opinion). Having started off quite enthused to have a paid writing gig during the Depression, Agee became un-enthused as a journalist after encountering the ‘starched clean for public consumption’ constraints put on his works by editors / publishers (including mogul, Henry Luce). Tasked in the mid 1930s with documenting the plight of Southern tenant farmers, his final article was refused. We are the better for it. This became: Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, an often rambling, occasionally dysfunctional odyssey of earth-scratching / entrenched rural poverty put to a lyrical, at times biblical rhythm (and of course, accompanied by Walker Evans’ spectacular B&W photography). The book is part documentary / part abstract art, wholly unique (especially for its day) and brutally honest. It often leaves no hope for humanity, then proves that we would probably survive any natural or man-made apocalypse fine enough – often pivoting between both inside a few paragraphs. It certainly is ‘something.’

In his day, he was probably best known as film critic for Time and more visibly The Nation during the 1940s. (Library of America published over 500 pgs of reviews in its Agee, Film Criticism and Selected Journalism; entertaining reading, though you have never heard of most of the films.) Posthumously, Agee is better known for a work of fiction and non-fiction … A Death in the Family was an unfinished manuscript fictionalizing the death of his father and the immediate moments and days afterward. It is stunning, incisive, lyrical and ultimately heart-rending. Despite missing Agee’s finishing touches, it was admirably pieced together by friends / editors and published. It won the Pulitzer in 1958 … But it is the work of non-fiction for which Agee is arguably most famous (or infamous, depending on the opinion). Having started off quite enthused to have a paid writing gig during the Depression, Agee became un-enthused as a journalist after encountering the ‘starched clean for public consumption’ constraints put on his works by editors / publishers (including mogul, Henry Luce). Tasked in the mid 1930s with documenting the plight of Southern tenant farmers, his final article was refused. We are the better for it. This became: Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, an often rambling, occasionally dysfunctional odyssey of earth-scratching / entrenched rural poverty put to a lyrical, at times biblical rhythm (and of course, accompanied by Walker Evans’ spectacular B&W photography). The book is part documentary / part abstract art, wholly unique (especially for its day) and brutally honest. It often leaves no hope for humanity, then proves that we would probably survive any natural or man-made apocalypse fine enough – often pivoting between both inside a few paragraphs. It certainly is ‘something.’

That is the life and art of James Agee condensed into two paragraphs. But a bio and full review of his catalog is not my goal here. I’m just looking to pay homage and stir interest. And so, to use Agee’s own classic phrasing: “We are talking now of two works of literary art” … James Agee composed the two pieces I have chosen to highlight at either end of his career. They are as bold and true as anything I have read; and even without my great admiration for most of his work, would alone elevate Agee into my favorites list.

The first we are talking about is, “Dedication” … a single chapter from Agee’s first publication, the short book of poetry, Permit Me Voyage (1934), written in and around his Harvard years.

The second is, “Knoxville: Summer, 1915” … a piece that opens A Death in the Family, which may not have been what Agee had in mind for the piece. But it is so natural a prelude it’s no wonder it was placed at the head of the novel. Still, it could and does stand alone.

PART 1 ›

“DEDICATION” … Its beginning is one of my all-time favorites:

To those who in all times have sought truth and who have told it in their art or in their living, who died in honor …

To those in all times who have sought truth and who failed to tell it in their art or in their lives, and who now are dead.

In its entirety, this work of poetry is more than just a dedication. It is without doubt Agee’s homage to those famous creative and spiritual leaders that have influenced him, and to those who have meant something to his life personally. (In fact the early lines seem written to purposefully document his love and praise, lest he forget inside the hustle of living.) It is equally, if not more so, an homage to the anonymous millions who have and will live worthy lives. But there is more to it. As is usual of Agee’s work, it turns on a dime: highlighting the beauty, the honorable, the praiseworthy, while noting the harsh, the indifferent, even the brutal. It is this deftness and insight to see all sides, whether fit for ‘polite-company public consumption’ or not, that made him a natural reviewer of books and film. “Dedication” itself turns from simple heart-felt homage to a klieg-light review of humankind. And yet in the twisting turning sprints to which he often subjected language, his harsh documentation is wrapped—however fatalistically—in the hope that we’ll make it through despite the unrepentant bloodthirsty bastards:

To those wiser who do not despise man in his doom, nor in the nature of his nature.

It is this twisting and turning that keeps me coming back to Agee, and “Dedication.” It’s a work of only a few pages: a dedication to those who deserve it, an apology for those active “merchants” of bad, a litany of examples for why we are a great species, with the harshest words reserved for those that make us ugly. It is an ode to the good, the bad, the indifferent:

To those who know God lives, and who defend him.

To those who know the high estate of art, and who defend it.

To those merchants, dealers and speculators … that they repent their very existence, as the men they are, and change or quit it: or visit the just curse upon themselves.

To those many who are indifferent to all semblance of truth.

This work acknowledges life as a miraculous masterwork of creation and an A-1 bitch from hell. And yet, despite the hard truth, I am still left with more hope than fear / loathing—that this mortal and spiritual experiment known as humanity really is working, if fitfully. This alone seems the reason why Agee saves up all his power of prayer for the ending, beseeching God to have mercy on us for what we are, and “preserve this people.”

Postscript:

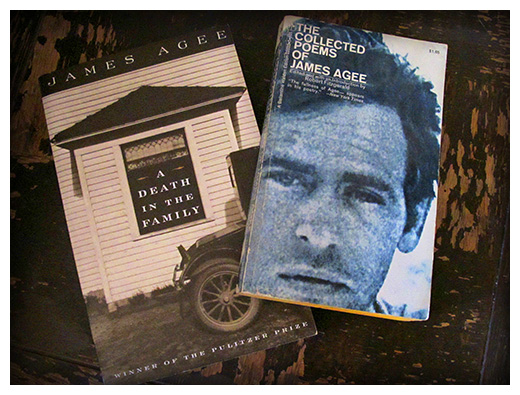

I’m not big on the idea of destiny, but have experienced enough highly improbable / fortunate moments to lean, on occasion, towards things being “written in the stars” … While on vacation in August 2004, I came across a paperback copy of Robert Fitzgerald’s collection of Agee’s poetry in a used bookstore in North Adams, MA. Obscure, out of print and only a few bucks, I passed. I regretted the decision only after we were too many miles down the road to go back … While on vacation in August 2007, I came across it again, same printing, on the shelves of another used bookstore, this one in Bridgton, ME. 3 bucks later, a past error was erased. Agee’s poetry was not included in the LOA set and as far as I know it is still out of print. I urge you to track it down in the library or used bookstore of your choice for “Dedication” alone.

PART 2 ›

“KNOXVILLE: SUMMER, 1915” … Here is language and a nostalgic ideal in perfect harmony. It is pitch perfect. It is only a few pages, but any longer and the scene and the reader might drift off. As written, it exists at the edge of a dream-state, that time of day when routines are leisurely and the sharp boundaries of time & responsibility fall away, slowly, evenly, towards night and inevitable sleep. The classic opening line:

We are talking now of summer evenings …

The working-middle class neighborhood, collectively finishing supper, cleaning up kitchens, sending out children into the waning light, the men—humble, yet proud—out to water their lawns. It is the picture-perfect scene of a more communal time before A/C shut all outside summer noises out, all inside noises in; long before TV and prior to widespread radio-use, when sitting on the porch or in the grass was entertainment enough. And though you are drawn into the time / setting, the piece does not rely on either. It is about mood and atmosphere, therefore timeless and easily exported. It relays the notion of an easy peaceful end to an otherwise normal day; substitute your own setting and details. I do easily. Whenever reading the piece, I catch myself drifting back through youthful recollections of like peaceful easy moments, hoping that everyone on Earth has at least a few such recollections to call up—sadly, knowing that a lot do not. And perhaps that is the ‘hard real’ of this piece, something which Agee made a career out of sliding in alongside ‘the ideal.’ If so, it is silently implied. The idea that such a perfect scene—the noise of water pouring from hoses and blending in a choral arrangement with the locusts and crickets, fireflies strobing, the night coming to rest in “one blue dew”—is a fleeting thing and not available to all (as sad as that is real) is, for this one Agee moment, distant if not entirely absent. It is simply a scene to be savored like “the last of their suppers in their mouths.”

The two reasons I have to believe that “Knoxville: Summer, 1915” was chosen to lead off, A Death in the Family—the novel a devastating antithesis to its idealistic intro – is that the piece was written with the child’s perspective in mind, and the father(s) are placed at the centre of it all. (The prose-like telling of the fathers watering yards is a full-third of the piece.) It is the child’s perspective that accounts for the dream-like state through which the whole piece is filtered, that time in the mind’s development when things are intensely noticed and observed and felt, yet not necessarily considered, defined and ordered. An ideal and harmonious moment is just intensely felt along with everything in the scene, regardless of meaning and reason, and imprinted on the mind with nostalgic relevance … But then, you know that this piece was written by an adult, one who has probably had to slog through the shit and often unrelenting challenges that awaits every child. This piece, written later in Agee’s life, echoes “Dedication.” But it leaves out the hardness a more resilient, more innocent youth can take in stride, focusing solely on the homage part: the positive. Nostalgia is the vehicle Agee uses to get there, to get us all there: to an ideal point in our lives when easy peace prevailed—if only for a summer evening—a time before life’s trials had worn deep ruts, before routine equalled dull repetition, before fathers had died.

A brief fictional / non-fictional recollection alleviating all ‘the crap’ for a moment, it seems to me that was Agee’s goal. The value of important nostalgic bytes become more valuable as more and more miles pass under the tires. They are a coping mechanism in line with laughter or fatalistic resolve … “Knoxville: Summer, 1915” ends with the young boy drifting towards sleep, lying on a blanket with all of his family, on the still damp grass, looking up at the night stars …

… who shall ever tell the sorrow of being on this earth, lying on quilts, on the grass, in a summer evening, among the sounds of night.

SOURCES:

The Collected Poems of James Agee, edited by Robert Fitzgerald; Ballantine Books, New York, 1970

A Death in the Family, Vintage Books-Random House, New York, 1998