Dave Buckhout .

Publication Date: 2005

Part I: The Rise of the Legend | Part II: The Fall of the Man

Introduction

There is a historic parallel between the African-American athletes of the early 20th century’s Negro Baseball Leagues and black jazz musicians performing during the same era. They share a common, regrettable bond. Both were loose-knit confederations that gave us some of the greatest talent this country has ever produced. Yet most all of that talent was forced to showcase their skills in second-class environments beneath the cultural plateau they deserved. These individuals comprise an indeterminate, largely anonymous list. One such man was hitting phenomenon Josh Gibson. If Gibson had the good fortune to be born fifty years later, he’d have a place alongside well known modern-day power-hitters who also hit for average. Those who do know his story have already placed him in the exclusive company of Hall of Famers: Frank Thomas, Mike Schmidt, Reggie Jackson, Hammerin’ Hank Aaron, Mickey Mantle, Frank Robinson, Stan Musial, Willie Mays, Ted Williams, Joe Dimaggio, Lou Gehrig and the Bambino himself: “Babe” Ruth. Josh Gibson is without question one of the best all-around hitters to ever play the game. And yet, so few do know his story.

Part I: The Rise of the Legend

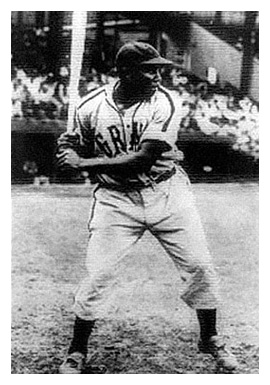

Credit: National Baseball Hall of Fame

In the story of Josh Gibson’s life it’s often difficult to tell where reality ends and legend begins. Along with his exceptional talent, a good deal of personal tragedy and his eventual self-induced destruction are very real. But the legend often overshadows all of this. The public exaggeration of “Gibson, legend,” by Negro League club owners, black and white sportswriters, even fellow players, began almost as soon as he began playing organized ball (“organized” a relative term when describing the notoriously loose structure of the Negro Leagues). But Gibson never seemed to give his celebrity status much air-time. He simply loved to play baseball. Off the field, his demeanor was almost reclusive. On it, his presence was intimidating. It is quite possible that Gibson himself just liked the “on field Josh” that he read about in the papers more than what he knew to be real. Either way, his notable indifference to the whirling publicity that followed him goes to suggest that his reality was an all-consuming one. Baseball proved to be his sanctuary. In The Power and the Darkness, author Mark Ribowsky writes: “. . . baseball, with its promise of emotional shelter, may have been Josh Gibson’s most obsessive, most rewarding, and most bedeviling narcotic.” His vices would eventually pull him down; but he made the most of his appetite for baseball. He was one of the fiercest power hitters of his era, black or white.

Josh Gibson was born in Buena Vista, Georgia, on December 21, 1911. In the early 1920s, Gibson’s father Mark moved to Pittsburgh in search of work in the steel mills. A few years later, he brought up the rest of the family and they settled on the north side of the city. By all accounts Josh was raised in a stable, but less than ideal environment. His mother drank, a disposition that would manifest itself in Josh soon enough. Gibson’s love of baseball kicked in during his teens. Aside from vocational schooling—which led to his first jobs as an electrician and factory hand—he was always playing pick-up “sandlot” ball; and playing it well. By the time he was 16, Josh had landed a slot playing with the amateur Pleasant Valley Red Sox. He also played for a team sponsored by the Gimbel’s Department Store. Gibson’s talent was obvious early. He treated pitchers rudely wherever he played. And this was being noticed.

In 1928 he met one of the two men who, for better or worse, would be central to his career. That year professional hustler, Gus Greenlee, put together the first of his Pittsburgh “Crawford” teams (named for a north side bathhouse). Greenlee scouted and pulled in local talent from the bustling amateur scene in greater Pittsburgh. . . . . Amateur baseball was an active feature of American life in the first half of the 20th century. Industrial / company leagues existed wherever they could field teams. These teams were a popular source of recreation and entertainment, even serving as a source of company and local pride. On occasion, they also served as an unofficial minor league farm system. (Possibly the most famous such recruit was “Shoeless” Joe Jackson, discovered while playing for a mill team in South Carolina). Greenlee utilized amateur teams throughout Pittsburgh to his advantage, filling the Crawfords’ roster by nabbing a lot of their best talent. Josh Gibson was one of his pick-ups.

By 1930 the Crawford “Giants” (their first team name) was a semipro fixture in Pittsburgh and the region, scratching by on meager donations taken in from “passing the hat” amongst fans. It remains a feat of endurance that the early years of the Depression didn’t wipe out “blackball” entirely—semipro and professional—considering the rationed financial state that all segregated teams were forced to endure prior to 1929. Many teams did fold. Few if any thrived, but a good deal at least survived the tightest years. The Crawfords were one, the team living a fitful life that saw them rise into the professional ranks of the Negro Leagues (this prior to a rapid collapse). The “Craws” competition would always be the Homestead Grays. Run by the slick, yet no less cunning Cumberland “Cum” Posey, the Craws and Grays would compete for the loyalty of Steel Town’s blackball faithful throughout the 1930s. And to that end, Cum Posey was already at work by 1930. No sooner had Greenlee assembled his impressive roster than Posey swooped in to play his own brand of hardball. Of course, one of the players Posey had targeted was Josh Gibson. The second owner that would be central to Gibson’s career—in the end proving more influential—Posey, not only found a willing young Gibson, but several blackball stars-to-be set to make the jump to the professional level. Common among the buccaneer-style racketeering atmosphere in which professional blackball owners operated, swiping or “raiding” players from rival clubs was almost a sport unto itself. And in 1930 Posey had the upper-hand, signing players virtually at will. 1930 would also be the first year of Josh Gibson’s professional career; and he would join one of the most formidable line-ups the loose-knit Negro Leagues would ever produce.

As mentioned, Gibson was a modest type off the field. The demeanor of his youth has been described as mellow and hard-working. In early 1930, he married his then pregnant girlfriend Helen Mason. He and his new wife, modestly, moved in with Josh’s parents—a necessity more than selfless choice. 1930 would bring the highest highs and lowest lows for Gibson. It would also view the beginning of the legend-making exaggerations that would always follow his career, starting with his first “pro” game. The legend has it that regular Gray’s catcher Buck Ewing hurt himself, and Gibson was called out of the stands to fill-in, thereby cementing his future behind-the-plate in the Negro “bigs.” Buck Ewing did split a finger in the first game of a doubleheader on July 25, 1930; but Gibson—aside from not being in the stands, enthusiastically jumping to the field and suiting up on the spot—was actually brought over from the Crawford Giants to catch the second Gray’s game that night. Though a deal was reached, Posey’s sway at the time was enough to publicly steal one of the top prospects from the known “numbers man,” Greenlee. With Gibson in his sphere, Posey would not let him go. Gibson performed well that first night, playing against the Kansas City Monarchs under the lights of Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field—certainly a thrill to the rising star. There were many more such games to come.

That was one of the highs. August 11, 1930, marked one of the lowest points in Gibson’s entire life. His wife Helen had endured a very difficult pregnancy, her life often in the balance. On that day in August she succumbed to a chronic kidney condition and died. Twins—Josh Jr. and Helen—would be born prematurely and live. But his young wife’s death was a devastating blow and clearly influenced his future problems. Helen would be Gibson’s only true love, though he would have other relationships. The remainder of Gibson’s life would view him as distant and removed from the life of his children (who were raised [even named] by their aunt, Helen’s sister). Most who have written about Gibson attribute this estrangement as much to the twins’ serving as reminders of Helen’s tragic death as to a personal irresponsibility that would manifest itself and ultimately consume the man. Providing financial support was one thing, but providing actual support in life to his children was not a part of the immense talent of Josh Gibson. Further, it is safe to say that this was the point when Gibson realized baseball could be his sanctuary; because he went right on playing through the tragedy and wound up having a very impressive “rookie” year for Pittsburgh’s Homestead Grays.

Gibson became an official Gray late that summer and was instrumental in helping them finish the year among the Negro Leagues’ best. World Series style championships had been at best spotty throughout the existence of blackball, often a result more of deals brokered between owners than a natural playoff system. Despite their place as two of the best teams, the end of the 1930 season saw not a championship but promotional series between the Grays and New York’s “Lincoln Giants.” A good deal of the 10-game series was held in Yankee Stadium. His talent on display in one of baseball’s hallowed halls, Gibson lit up the Lincoln Giant’s pitching staff. One homerun hit in the Stadium was measured at nearly 500 feet. It was the longest homerun recorded there that year, in any league. Later dubbed the “blackball shot heard round the world,” that one hit did more than any other accomplishment in launching the legend. There would many more “moonshot” homeruns to come too.

To students of the game, descriptions of Gibson’s play reflect a natural fundamental soundness—as if there was little thought involved. It does seem he played the game on an instinctual level, as if it was what he was put on this earth to do. At his prime, Gibson was 6’ 2” 190 lbs. Crawford player-manager Hooks Tinker compared him to “sheet metal.” He was a muscular mountain of a guy behind home-plate and was so strong that he swung a 40 oz. + bat (the standard today is in the low 30s). Two different takes on his stance and swing give us an idea of what it must have been like to watch him. In his biography of Gibson, William Brashler describes him as standing upright, flat-footed, relying on upper body strength, a short stride, a compact swing. Being so compact and quick Gibson was rarely fooled, for he could wait on a pitch longer than most. Ribowsky records the second description of Gibson, given by Tinker: “He was like a reflex, a nerve jumpin’ all at once.” He was smart about “going with a pitch” away and “inside-out” on a pitch inside. In other words he could adjust, a sign of an intelligent hitter. One reason was the strength of his wrists. He could simply muscle a ball without relying on leg momentum and stride. He had an accurate eye (represented in his outstanding on-base percentages); and as mentioned could hit singles and doubles, as well as monstrous tape-measure homeruns. What is often overlooked is the fact that he was a pretty good catcher, as well—which is without argument the toughest position to play day-to-day. Gibson worked hard to improve as a “receiver.” It shouldn’t be a surprise that he took to the basic skills required to catch rather instinctively: developing a rifle arm for throwing out runners and a shrewd understanding of how to strategize pitch selections—keeping hitters guessing, thereby keeping the advantage with his pitcher. He had All-Star qualities across the board. Inside of a year of joining Homestead, Josh Gibson was one of the most recognizable Negro baseball stars.

The single most recognizable name in Negro League history came to Pittsburgh in 1931, that being Satchel Paige. The careers of Paige and Gibson would be linked in their timing. The two would be teammates, but would more often lock horns as competitors over the next fifteen years. Paige was to blackball pitching what Gibson was to hitting, i.e. the best. But there the similarities end. A smooth-talking master of self-promotion, Paige was his own man—a condition clear to every owner who ever signed him to a contract only to see him skip out for a week or two at a time on barnstorming tours across the country. These trips were always lucrative, Paige showing up to don his contracted team’s uniform just in time for a highly anticipated meeting of two top clubs, or a big weekend series where the draw at the gate promised better revenue. This aside, Paige could pitch. Rare was the night that he didn’t roll through formidable Negro League line-ups. His uncompromising taunts and biting wit were often enough to rattle anyone inside the batter’s box, Gibson included. But Paige was full of praise for Gibson in recalling his one-time battery-mate, Brashler recording this comment by Paige on pitching to Gibson: “You look for his weakness and while you looking for it he liable to hit 45 homeruns.” Paige’s uncompromising autonomy was a common condition of the Negro Leagues that just did not occur in the rigid monopolistic all-white Major Leagues. Blackball advanced a notoriously loose structure, to the point where actual leagues ascended, faded, added and subtracted teams on a yearly basis. For many years during the 1920s, there was no official Negro League. No doubt the financial reality of Jim Crow America was the main factor, that and the institutional clampdown on any form of black autonomy and / or enterprise (Ribowsky referring to it as “. . . the plantation of segregated baseball”). This loose fly-by-night nature led to conditions that seemed hardly legitimate. But the one thing that does seem fair is that at least the players realized this too. One only had to look to Satchel Paige to be reminded: “to the entrepreneurial went the spoils.” As if the player raids of competitors weren’t bad enough, owners often watched signed talent disregard contracts and “jump” to another team that would offer more money. In comparison to the Major Leagues—in which players were ironically much more like slaves to their owners—blackball players had a certain amount of leverage in tune with their level of talent, Ribowsky summarizing it well: “all [Negro League] players were free agents.” A major issue would be the enticement and draw of African American ballplayers south-of-the-border, where decent pay in the Caribbean Islands, Mexico, Central and South America was augmented by cultures that advanced no bias towards these talented black athletes. In fact, it was quite the opposite: they were treated like kings. Both scenarios were in the immediate future for Gibson, Satchel Paige no doubt introducing both contract autonomy and out-of-country opportunities to him and other blackball stars—if only by example. Gibson would grow more bold in pursuing said opportunities as his star ascended. But Josh Gibson found life as a pro in Pittsburgh comfortable enough during the early-mid 1930s. His homerun totals reflect as much.

Over the next few years Gibson confirmed the buzz, littering outfield stands with homeruns wherever he played. Most were on small stages, non-league games across Pennsylvania, the Midwest and the South. One such was in Moneseen, Pennsylvania, the ball exiting the stadium entirely, traveling well over 500 ft.—the distance confirmed by no less than the mayor of the town. In the mid 1930s, Gibson would begin to dabble with baseball south-of-the-border, playing in winter leagues. During one particular tour in Puerto Rico he crushed another 500 ft. stadium-busting homerun that landed in an adjacent prison yard. But there were some grand stages that brought much publicity to the legend. One in particular was a blast in Chicago’s Comiskey Park, at what would become an annual East vs. West Negro League All-Star Game. The homerun is rumored to have exited the field on a line drive and stuck in a loudspeaker, again some 500 ft. from home plate. It was no secret that Gibson loved to play at Yankee Stadium; and rare was the time that he didn’t give the segregated fans in attendance something to remember. . . . . Many of the blackball stars from the time wished to show their skills not only to a wider audience but to prove them to white Major Leaguers, the opportunities missed just part of the larger social failure that allowed prejudice to relegate athletic equals to second-class status because of skin tone. Yet under what were often humiliating conditions (Grays players were not allowed to use the Major League Pirates’ locker room at Forbes Field having to suit up down the road in a YMCA, the bigoted slights they experienced barnstorming the South too numerous to list) these individual talents plied their skill with admirable toughness. The rough-and-tumble dealings of Negro League team owners found its way onto the field. It was by all accounts a more physical, scrappy brand of baseball: base-stealing, spitballs, slight-of-hand, hit-and-run, overt taunting, etc. Power hitters like Josh Gibson were not as prevalent as the homerun laden Majors, which is perhaps why his star stood out. But then 500 ft. homeruns would certainly make a player stand out, Gibson reported to have once said: “A homer a day will boost my pay.”

Gibson first asserted the mentioned autonomy prior to the 1932 season. A day after signing to play for Cum Posey that year, he jumped to play for Gus Greenlee’s Crawfords. The pay increase would net Gibson $100 extra per month. Having acquired Paige the year before—on what was in reality a part-time basis—Greenlee now had the two most famous blackball stars on his team. His influence changed over night. One of the draws for Gibson was Greenlee’s construction of a stadium for the Craws. Greenlee Field would open in late April 1932, making the Crawfords one of the very few Negro League teams to ever have their own “home.” Rankled, but without legal clout, Posey had to watch Gibson go. And Gibson, feeling his new found freedom, had a break-out year. It almost didn’t happen at all. On the way to the Crawford’s spring training camp in Hot Springs, Arkansas, Gibson’s appendix burst. It was successfully removed, and Gibson recovered fast enough to accompany the Crawfords on a major barnstorming tour during the first half of the season. It was quite the tour, games played against every level of competition—a number of the biggest draws against Negro Southern League teams like Birmingham and Nashville. In all the team logged 17,000 miles, playing 94 games by July. This kind of schedule was not uncommon and required a great deal of personal toughness, black ballplayers most often forced to eat poorly and stay in segregated dives while on the road. But to Josh Gibson and most of his cohorts they would rather be doing nothing else. The year was good to Josh, if not blackball in general (the defunct Negro American League having been replaced by the Posey sponsored Eastern League, which likewise folded). The Craws had become a dominant team overnight, even dispatching of the Grays in multiple series that year; a bad year for Cum Posey, but a good year for Gibson—who aside from hammering pitchers all year added another 500 ft. + legendary blast to the grist of legend, this one coming against a semipro team in York, Pennsylvania. Josh Gibson would finish the year near the .380 mark, with 40 + / – homeruns. The Crawfords, having assumed the title of best Negro League team, finished with a remarkable—if unofficial—99-36 record. That winter, Gibson went to the Caribbean for the first time. It would be the first taste of a life that would eventually consume this monster talent.

Part II: The Fall of the Man

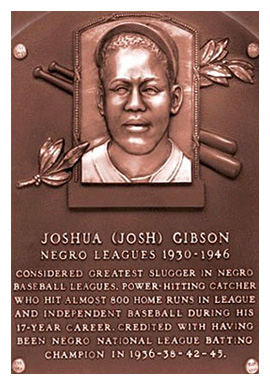

Credit: National Baseball Hall of Fame

By the end of the 1932 “regular” season, Josh Gibson was an ascending star like few that had ever emerged from the Negro Leagues. The only thing that kept him from being a star in the all-white Majors was the color of his skin. There is no doubt that Gibson would have mauled white pitchers as he did those unfortunate African American / Latino pitchers who shared his second-class stage. It is well documented that Gibson dreamed of the day when baseball would come to its senses and measure individuals on the quality of talent, not their shade. But each year offered instead the promise unfulfilled. There was always next year; but then it would come and go. And aside from the occasionally bold op-ed of a sportswriter pushing for it, the notion of big league integration would evaporate. It is unfortunate but accurate to say that many of the Negro League stars had come to live with it. Whether Josh Gibson ever did remains questionable. But thanks to the reconnaissance of Satchel Paige and others, many of the Negro Leaguers had found an eager opportunity in the meantime. South-of-the-border businessmen, politicians and even small-time dictators were putting out the call to blackball stars. Starting with winterball, these players began to venture to the Caribbean, Mexico and South America. With the meager pay (in comparison to the Majors) earned on the fields of organized Negro League baseball, a year-round schedule and steady paycheck were requirements. But the added enticement of high-living and hero worship like no black man could attain in America, erased such functional considerations. As William Brashler writes in his bio of Gibson: “. . . [Negro League] players were idolized and shown none of the discriminatio they saw as a matter of course in the States . . .” During the winter of 1932, Josh Gibson suited up for winterball in Puerto Rico. It would be his first taste of a lauded partying lifestyle that would eventually consume him.

The mid 1930s were good to Gibson and Greenlee’s Crawfords. And despite the penury depths of the Depression, they were also good to blackball. The Negro National League (to which both the Craws and Grays belonged) found new life after collapsing. It became the dominant league, with teams from New York to Chicago. The Southern League (which included Nashville and Birmingham) eventually fed teams into both the NNL and Negro American League. (The NAL’s marquee team would always be Kansas City’s Monarchs, especially after adding Satchel Paige.) At a time when no one could have faulted the professional game for contracting, if not folding outright, professional baseball—and even more impressive—professional “blackball” thrived. The game was a distraction from the long bleak days, a national therapy for blacks and whites. It has been accurately documented that the Depression didn’t change economic conditions much at all for the majority of African Americans. Most had known nothing other than institutional poverty as a matter of course. This certainly played a role in keeping blackball alive during the Depression. But in the end, the credit has to go the players. These guys could play. The Gibson-Paige rivalry, the growth of professional leagues / teams and more regular end-of-season playoff series all added new life to the black game. It brought fans through the turnstiles. But perhaps the most significant feature of all was the East vs. West All-Star Game. Under Greenlee’s shrewd command, the NNL had been revived; but his legacy would always be embedded in organizing what would become the annual Negro League classic.

The first All-Star Game was held in Chicago’s Comiskey Park in 1933. As mentioned, Gibson crushed a monster homerun that rumor has it stuck into a loudspeaker beyond the outfield fence. By this time truth and legend were often one in the same when it came to Gibson. A lot of this was due to the sportswriters of regional, and distant, black newspapers. Both Greenlee and Posey would virtually employ local writers, who in turn showered their respective players and teams with praise and legend, earned and exaggerated. Posey himself would often contribute a column to the Pittsburgh Courier, always ratcheting up the hype of his stars with salesman-like streams of adjectives. In this is the age-old tactic by which great talent ascends to immortality. What is often lost is the human at the centre of the tale. Yet in Gibson’s case one can hardly fault the sportswriters and various owners for elevating Gibson as something above human (despite the rapid manifestation of his off-field “humanity”). For his years with the Crawfords during the mid 1930s were just astounding, statistically. In James Riley’s impressive, definitive encyclopedia of the Negro Leagues, he lists Gibson’s “official” batting averages from 1933-36 with the Craws as .464, .384, .440, .457—these alongside “Ruthian” homerun totals: 69 in 1934 alone. Those are indeed superhuman numbers. For sure, Gibson faced some weak pitching during that time. But he also faced Major League caliber hurlers denied their place in the “bigs” for the same reason as Gibson. The pinnacle of the Negro Leagues was just as capable as the segregated Majors. And like the Majors: talent got your there and the repetitive showcase of that talent was required to keep you there. Even knocking fifty points off the mentioned batting averages would have put Gibson in the yearly batting title hunt; and there was rarely another player—white or black—that could put up his homerun totals. In the end, Josh Gibson would prove human through-and-through; but a great deal of the legend-making was justified.

Gibson’s final two tours with the Craws in 1935 and 1936 proved two of his finest years. Mark Ribowsky documents one-after-another illustrious achievement, among them: a .500+ average for the month of July 1935, and a monster homerun in early 1936 against the Philadelphia Stars that entirely exited Philly’s spacious Parkside Stadium. As had become ritual, he and Paige were the star attractions at the East / West games during that time, leading a cast of exceptional talent who sported such character-laden names as: “Turkey” Stearns, “Mule” Suttles, “Cool Papa” Bell and the versatile Cuban right-hander, Martin Dihigo (who also regularly led the old Negro AL in homeruns during the late 1920s). Gibson’s bat went on to lead the formidable Pittsburgh team to the 1935 NNL pennant—beating out Dihigo’s New York Cubans in an end-of-season 7-game series—then repeating the feat in 1936 (on record, as a ’36 playoff series did not materialize). It is regularly stated that the Greenlee-assembled Crawford team of the mid 1930s was the greatest Negro League team of all time. With perennial all-star “Cool Papa” Bell, the occasional addition of Paige, Gibson, the solid centerfielder Sammy Bankhead (who would play an increasing role as Gibson’s drinking chum), a number of other star players and many claimed championships, the case is well made. They are at least entitled to share the honor with Rube Foster’s great early 20th century Chicago Giant teams. And as Foster was always the core of his teams (for which he both played and managed), Gibson was always the core of the Craws’ successful teams. Cum Posey would have certainly agreed. Having been forced to play second-fiddle to the shrewd Greenlee, Posey felt the time had come to make his move—which he would do prior to the 1937 season. No doubt laying the groundwork for a “raid” he hoped to make, Posey wrote this October 1936 column in the local Courier—which seems intended as more publicly flattering than factual:

“. . . Gibson is the only Negro player of the 1936 season whom we are certain could step right into the National or American [Major] league and make good as a regular without the usual procedure taken by white players through minor leagues.”

Certainly there were many blackball stars that could have “stepped right in.” But with Gibson this was a foregone conclusion. Not only could he have stepped in, he could have dominated. At least some proof of this was provided via the admirable and popular post-season traveling series St. Louis Cardinal great Dizzy Dean had helped organize, in which non-biased and willing white all-stars locked horns with blackball all-stars. More exhibition than anything, Gibson nonetheless shelled the white Major Leaguers he faced, including Dean himself (who was full of praise for Gibson and truly seemed to have enjoyed helping provide blackball’s most talented a stage). In retrospect, it seems impossible that Gibson’s legend-making talent could have been anything but dominating in the all-white Majors. And amongst the many nicknames that had been hung on the slugger (“fence buster,” for instance) one did and still does stand out given the history of race and its effects on this country—that nickname being “the black Babe Ruth.” By this point in an increasingly Hall-of-Fame-worthy career many had begun to wonder if Babe Ruth was not the “white Josh Gibson.”

A number of things played a role in setting Josh Gibson on the road to alcoholism. The tragic loss of his wife so early was most certainly a factor. Baseball and booze provided a ‘sanctuary’ from the pain of an event that would have devastated anyone. It doesn’t seem that Gibson ‘the man’ ever came to terms with that loss, the numbing nature of heavy drinking and his lifelong estrangement from his children being proof enough. It also seems evident that Gibson drank to escape the public eye, an escape for sake of an escape—ironic, in that stumbling drunks are more often at the centre of the public eye. Yet in this seems to reside the underlying factor that drove him to drown his life, and immense talent, in drink: genetic disposition. As mentioned his mother Nancy was a chronic alcoholic. Tragedy and a reclusive nature seemed enabling features in Josh Gibson’s life, dual triggers of a loaded gun. Yet the number one enabler seemed to be that which sent him over the edge: his freewheeling, largely unsupervised stints as a baseball king south-of-the-border. All accounts of his and the majority of other Negro League players’ winterball days can be summed up as ‘playing all day, partying all night, repeat.’ The number one concern of the owners / businessmen / politicians who enticed blackball’s greatest to come and play, from the Dominican Republic to Mexico to Venezuela, was the happiness of the players. Little expense was spared, from women to liquor, even illicit drugs. Curfews were common, but were openly flaunted, especially amongst the top talent. And Gibson was certainly considered tops.

During this time Gibson had begun to see another woman. Hattie Jones would seem to be his first serious commitment since Helen’s death. Josh and Hattie were together from 1934 on, eventually moving as a couple into a house Josh had bought. Hattie was said to be relatively cold and controlling. It’s hard to see what the relationship brought either of them, for it seemed rarely affectionate (it was often hostile) and just as rarely functional A reasonable explanation could be that in the back of Gibson’s clouding mind, he knew he needed a rudder—a tragic, yet common trait amongst chronic alcoholics who are literally powerless to their addiction. Still, it’s unclear that Hattie was willing to serve this role. It’s equally difficult to discern if Josh really did feel this way about Hattie, considering his having gained public recognition as a womanizer—a trait that gained momentum in step with his alcoholism. If Hattie was a stabilizing presence for Gibson that role went unfulfilled during winterball, as Hattie stayed put in Pittsburgh. Without anyone to steer him straight, his fellow Negro Leaguers often complicit in the non-stop partying, Gibson drank, played ball and drank some more. It seems safe to say that Gibson’s winterball stints in the Caribbean were quite often blurry ones.

Cum Posey had again set Gibson in his sights. Since Gibson had gone to the rival Crawfords, Posey’s Homestead Grays had been a fairly mediocre presence in the NNL. With Gibson they could regain their prominent position. As mentioned most Negro League contracts were year-to-year; and even then were quite reliant on the fidelity of the player. In early 1937, Pose made his move to lure Gibson. Despite the consistent success of his team, Greenlee was always wracked by debts. His underworld business enterprises seemed always about to catch up to him. He was most certainly involved in a thrown game the previous year against a team from Brooklyn, which when the payoffs and returns-on-bets were ‘outed’ became a big scandal (as well as underlining the gambling style of many Negro League owners, and players). It may have been those hovering debts that forced Greenlee into what amounted to a trade with Posey: two players and $2500.00 to Greenlee, Gibson to Posey’s Grays, was the deal. Posey, set to reclaim his title as owner of the Negro League ‘team to beat,’ had to be on top of the world. But Gibson had other plans. The autonomy of the blackball stars is probably best illustrated by the “raid” that led off the 1937 season. Rafael Trujillo was the small-time dictator of the Dominican Republic. That spring he subsidized creation of a world-class baseball club to represent him against all other Caribbean takers. Gibson was targeted, along with Paige, by agents sent north intent on bringing back Negro League talent for the dictator. No sooner had Gibson signed with Posey, than he jumped at princely 7-week long contract offered him by Trujillo’s agents. A number of NNL stars followed Gibson and Paige to the island for two months of tightly controlled, but highly lucrative play, leaving a string of red-faced owners in their wake. There was talk of lifetime bans and stiff fines and lawsuits amongst the NNL owners. But in the end—perhaps realizing the shady nature of their own dealings—there was little that the owners could do. After proving the greatness of Trujillo (via the greatness of his Negro League imports), blackball’s most talented returned stateside to join their former clubs. On the side, Posey insured Gibson’s return by guaranteeing no action would be taken against the slugger. And living up to expectations, Gibson came back and helped a solid Grays squad win the 1937 NNL pennant. He punctuated all of this by crushing a legend-making homerun in Baltimore’s “Oriole Park” that July. The irony bears repeating: that blackball stars had so much more freedom over where and when they played than their white counterparts in the Majors. And yet, it was the Majors where blackball’s best wanted to be.

The late 1930s / early ‘40s were full of speculation of an integrated Majors. True of Gibson’s entire career, the prospect hung over each season. It was especially close to the elite talent of the Negro Leagues, who knew racial mores to be the main factor keeping them from the big stage. In step, speculation that this was the chief reason behind Gibson’s alcoholism—which did seem worse with each passing year—is standard (and not unjustified) thinking amongst those who have written about Gibson. It was certainly a piece to the complex puzzle that worked inside his head. That the Majors seemed forever beyond his reach had to weigh heavily. By that point the Grays were actively splitting their time between Steel Town’s Forbes Field and D.C.’s Griffith Stadium, home to the Major League Washington Senators. These grand stages, along with the Gray’s many trips to and displays put on by Gibson at Yankee Stadium and the Polo Grounds (one of his favorites due to its “short porches”) in New York and other Major League stadiums from Philadelphia to Cleveland to Chicago, had to be equal parts thrill and let-down. This in light of the increasing amount of favorable press white Major Leaguers were providing blackball stars. Starting with Dizzy Dean in the mid ‘30s, many white players were coming to see social inequity as hurting the game. In 1939, New York Giant great Mel Ott was quoted as saying: “From what the other big leaguers tell me, they [blackball stars] must be good enough for the majors.” Tacit endorsement, yes; but for the time that was a big statement. Ultimately more deflating for Gibson was the quote of Senator’s star pitcher Walter Johnson, who was getting ample opportunity to watch “the black Ruth” showcase his immense talent. Johnson said: “There is a catcher that any big league club would like to buy for $200,000 . . . Too bad this Gibson is a colored fellow.” The 1939 season saw two Negro League all-star games, the second of which was played at Yankee Stadium. Gibson’s play was so impressive both at and behind the plate—on this: the grandest of baseball stages—that it drove N.Y. Daily News reporter Jimmy Powers to write: “I am positive that if Josh Gibson were white he’d be a major league star.” Mark Ribowsky makes the point that perhaps social standards weren’t the only items at play in maintaining segregated pro ball, that blackball owners—despite public exhortations favoring integration—were “knee deep in the business of baseball apartheid.” It’s hard to argue. Without their African American / Latino stars the owners would have been forced to find other work. And so, it really is to Gibson’s credit that with such routine disappointment, he nonetheless put together a Hall-of-Fame career. Indicative of his all-out effort was his continuing to play through an infected “strawberry” received from a slide in June of 1939. Baseball was simply his world. He wanted to play every day whether feeling sick, hungover, or great.

Each and every year, wherever he was, Gibson put up mammoth stats. The 1939 season viewed the legendary Monoseen blast, and saw the Gray’s just miss their third-straight pennant, losing an end-of-season championship series to Baltimore’s Elite Giants in seven. It would have been the Gray’s third straight pennant, and Gibson’s fifth (including his years with the Craws). 1939 also saw the end of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, Greenlee’s brother having sold the team (which relocated to Toledo and then Indianapolis before quietly folding in the ‘40s), with the one-time jewel of the Negro Leagues: independently owned / operated Greenlee Field, demolished before the season had even begun. The way that teams appeared and disappeared, and owners went from boom-to-bust—alongside the shifting loyalties displayed by many of the players—all seems indicative of the constrained economic conditions within which blackball was forced to operate. In this, one can hardly fault Gibson for again deserting the Grays—and perhaps his unrealized dreams of playing in the Majors—to play the 1940 season in Venezuela. The pay was lucrative and again he lived “high on the hog.” Fed up with south-of-the-border player raids, Posey and other owners had begun singling out Latino scouts and booting them from the games, often with a few other unpleasantries thrown in. But it did little to slow the “defection” of many blackball stars from the two functioning blackball leagues: the NNL and NAL. When Gibson and his now inseparable drinking partner Sammy Bankhead “jumped” to play in Mexico in 1941, Posey had finally had enough—threatening to sue and put a lien on Gibson and Hattie’s house in Pittsburgh unless the slugger came back. If the threat was ever more than that, Posey eventually backed off. And perhaps his Grays were better off that year without Gibson, for he and Bankhead were reported to be drinking themselves stupid down in Mexico.

The following year brought the U.S. into World War II. South-of-the-border ball was suddenly less appealing in a more hostile world and illegal if one was eligible for the draft. Gibson, on account of knees hobbled from catching for so many years, was labeled 4-F: not fit for military service. His return to the Grays in 1942 revealed the first signs of a rapid physical deterioration brought on by his alcoholism. (Rumors, which would prove true, also included increased drug use.) Nonetheless, 1942 proved an exciting year for both Gibson and the Negro Leagues. The higher wages to be had working in defense industries were open to African Americans; and the increase in disposable income became prevalent with record crowds turning out for big blackball events. Crowds in excess of 30,000 were tallied on a regular basis for the first time in the Negro Leagues’ existence, with over 40,000 attending that year’s East vs. West All-Star game. In step with the Leagues’ newfound popularity, the first Negro League World Series since the 1920s was held that year. The Grays, behind Gibson’s slower but still hearty enough swing, represented the NNL. They would go down to Satchel Paige’s upstart Kansas City Monarchs of the NAL, but not before massive crowds got to enjoy the renewed rivalry of Satch vs. Josh (Satch coming out on top in this round). It was a resurgent year for the black game. But there was a flip side: 1942 showcased the beginning of a slow decline that would end in Gibson’s untimely death.

The final piece to Gibson’s undoing was his involvement with Grace Fournier. By 1943, he was basically avoiding Hattie Jones, his kids, and all his ties in Pittsburgh—the Grays playing most all of their “home” schedule in D.C.’s Griffith Stadium. And that’s where Gibson met Fournier, the night-clubbing wife of a serviceman then overseas. Josh was instantly taken. He was most likely more seduced by the vices she brought with her. Mainly clandestine, the relationship was just what Josh Gibson did not need. It further enabled a licentious destructive lifestyle bent on addiction. Worse, it’s said that Grace brought heroin into the mix. To what extent the star went with heroin is unclear; but it takes very little to get hooked, and once hooked the drug destroys from the inside out. If Gibson’s return to the Negro Leagues in 1942 had showed the first signs of his lifestyle rendering a physical toll, 1943 only helped to increase the pace. Early that year, Gibson landed in the hospital with what was called exhaustion, most likely the results of alcohol. During evaluations of his condition, it was rumored they had found a brain tumor. This was kept silent. Aside from (possibly) the doctors, Josh was said to have shared this deflating news with only his sister; which does seems strange, considering how aloof he was with his biological family, and kids. As with many facets of Gibson’s life, this whole event is not entirely clear. But being enigmatic, if not reclusive, was a natural trait. Such mystery often allows for legend. But that would come later. The mid ‘40s were, sadly, all about the self-destruction of ‘the man.’

Teammates, rival players and all those close to Gibson openly remarked about the star’s bloated weight gain, how drained he always looked and how he just seemed to have ‘aged overnight.’ It was common knowledge that the standard team rules about drinking did not apply to Josh. He drank on the bus rides, was often hungover, was said to be a regular at ‘the sanitarium’ and was even caught drinking in the bullpen during a game in 1942. With the addition of Grace Fournier to his life, his erratic behavior became more pronounced. She would prove a lethal presence. And yet despite all of this, he hit over .400 during the 1943 season and continued depositing monster shots into outfield bleachers. 1943 also provided Gibson with a June “peppering” of Satchel Paige—in which the Grays knocked Paige out after only three innings—the Posey-inspired Josh Gibson Appreciation Night, held September 9th at Griffith Stadium, and even a marquee Time magazine article about the black star titled, “Josh the Basher.” By all other standards it would have been a banner year. And from the plate it certainly was. But perhaps the first area of his game where poor physical condition had begun to inhibit his play was behind-the-plate. For the remainder of his career he would go into more of a standing crouch when receiving than assuming the standard, physically demanding bent-knee position. Not much has been written of Gibson’s fielding late in his career. One has to figure it suffered mightily. But his fielding was of little concern as long as he could hit; and it is commonly written that “if he could stand he could hit.”

Josh Gibson’s story is a depressing one to conclude. He went downhill steadily through the mid ‘40s, but amazingly continued to put up big numbers at-the-plate. Gibson and fellow bomber, Buck Leonard (they were called the “Thunder Twins” and eventually given the more prestigious stamp: the Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig of the Negro Leagues) were integral to the Grays winning NNL pennants from 1942-1945. They also defeated the Birmingham Black Barons for the whole deal in ’43 and ’44 (Gibson putting up a .400 average in the ‘44 series). Gibson, who had begun to sit out games more regularly, still got up for the big ones. In 1944’s East / West game he hit a monster shot off Satchel Paige that struck a clocktower at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. His swing had slowed noticeably, but he still managed to lead the league in homers in 1945. The Cleveland Buckeyes surprised the Grays by sweeping that year’s N.L. World Series. But there was a bigger surprise on the horizon. In October 1945, it was announced that the young Kansas City Monarch star, Jackie Robinson, would step into the Brooklyn Dodger’s farm system in 1946 and into the white world of Major League baseball. He would be the first African American or Latino to play in the Majors since the 1880s. The news meant different things to different black players. To the younger players, such as Robinson and Baltimore Giant’s star catcher Roy Campanella, it was a new world of opportunity. To the older players, such as the fading Gibson (who was only 34), it meant integration about a decade too late. Whether the news of Robinson’s signing produced a significant change in Gibson’s attitude is debatable. Regardless, his physical decline was evident during the following season. The 1946 Negro League season was played in a kind of suspended animation. Players knew its days were likely numbered. Owners were left with the hope that, at best, they could transition into an independent farm system. It was reported that Clark Griffith, owner of the Washington Senators, had once approached the enthusiastic Gibson and Leonard about playing in the Majors; but nothing even came of it. It is quite likely that Griffith sought an inside track to the talented Homestead Grays, given the regular talk of integration. However, a pioneer Griffith was not and the two blackball sluggers never did make the Majors. 1946 would in fact prove the final tour for Josh Gibson. And despite looking like “death walking,” he made the most of it, leading the league with a .360+ average. Yet his vices—including Grace Fournier (who had unceremoniously dumped Gibson with the return of her husband at war’s end)—had destroyed his body and his mind. He was often incoherent and many began having trouble telling whether he was drunk or sober. Worse still, he had developed a kidney condition. He got worse during the off-season. Too sick to consider winterball, Gibson was forced to move back in with Hattie Jones. This would prove the only extended period of time (only a few months) that he ever spent with his children. But his deteriorating physical ailments, and the fact that his lifestyle had left him all but broke, forced him into even more desperate straits. He was forced to move back in with his mother. The next January a very drunk Gibson stumbled into an afternoon matinee at a local theatre. He was later found unconscious and taken to the hospital. Josh Gibson died quietly of a brain hemorrhage the next morning: January 20, 1947. He was only 35.

Josh Gibson is credited with around 900 + / – homeruns in both league and non-league play. He compiled a lifetime Negro League batting average over .350, with averages south-of-the-border considerably higher. He was a giant of the game. And yet he was sequestered to obscurity. As if symbolic Gibson was buried in a cemetery near the Pittsburgh neighborhood where he had lived most of his life, with only a numbered metal plaque supplied by the county to mark his grave. Though most often warm and personable, well-liked by his teammates, Gibson’s inner demons were plentiful and still are not entirely understood. Perhaps William Brashler put it best when he wrote: “[Gibson’s] death, though tragic, was not that of a fighter but of a victim.” . . . . In 1971, Major League Baseball began the process of reconciling its past. That year Satchel Paige became the first Negro Leaguer to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. In 1972 Josh Gibson became the second, going into the hall with Yogi Berra and Sandy Koufax. Soon after a drive was organized to provide Gibson a proper headstone. The MLB commissioner’s office paid the bill. Though failing to honor his talents in life, the game did so in death. Alongside the cultural futility of one of the game’s legendary hitters, it almost seems fitting. But then allowing Josh Gibson his rightful stage would have been the only true justice.

Bibliography:

Brashler, William. Josh Gibson, A Life in the Negro Leagues. Chicago, Ivan R. Dee: 1978.

Holway, John B. Blackball Stars, Negro League Pioneers. New York, Caroll & Graf Publishers: 1988.

Ribowsky, Mark. The Power and the Darkness. New York, Simon & Schuster: 1996.

Riley, James A. The Biographcial Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues. New York, Carroll & Graf Publishers: 1994

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, NY

The Negro Baseball Leagues Museum, Kansas City, MO