The elaborate grounds of Chatham stand along the low ridge east of the Rappahannock River known as “Stafford Heights.” Set on a plantation dating to 1771 and owned by James Lacy in the 1860s, this simple Georgian looks over Fredericksburg across the river and the low shore before it and to the right—the area where on December 11, 1862, U.S. engineers laid down the “upper” pontoon crossing. One of three crossings begun in the pre-dawn that morning, this engineering effort marked the end of a three-week period of often contentious brooding among the Union brass. Lee’s army held an established defensive position. But the ornately whiskered Burnside (and yes: the term “sideburns” is attributed to the general’s famous facial hair) hardened on the improbable success of putting The Army of the Potomac across the river and driving through the Confederate lines. Most of his high command thought the plan reckless, even foolish. When Burnside sought a sidebar opinion, an aide grimly stated: “it will be the greatest slaughter of the war.”2 Spurned, and likely seeking the prideful solace of a “yes-sir” man, Burnside turned to Lt. Colonel Joseph Taylor, who could only elaborate: “The carrying out of your plan will be murder, not warfare.”3 Yet with pressure from Washington mounting, Burnside felt compelled to act. The army would cross the river and attack. Orders were issued and word began to circulate amongst the ranks. A Capt. Wesley Brainerd penned a letter to his father, lamenting, “Dear Father … Tonight the grand tragedy comes off.”4 And so did The Battle of Fredericksburg proceed.

With the sheer tonnage of literature that has and continues to be produced on the war, and the regularity of historical fact superseding narrative style, I find it difficult to turn up those few volumes that can do both. In pursuit of such works, I make it a point to seek the opinions of NMP rangers. On the 2003 tour, the answer to this question was: “as far as Fredericksburg is concerned look no further than Frank O’Reilly’s, The Fredericksburg Campaign.” I received my signed copy a month later and ran it through. As mentioned, its tight detail and weave of solid narrative combine to make this a signal work. But I also warmly recall the rest of a lengthy conversation with the ranger, who among other things answered a question Dad had earlier posed to me and for which I did not have a ready answer: “what was the alignment of cannon ‘in battery’ ?” The ranger informed us that it was 14’ apart, going on from there to summarize the procedure for laying a Civil War-era pontoon bridge (Dad having served in the Army Corps of Engineers). I also recall making note of his suggestion for further reading: O’Reilly’s details of the U.S. engineers’ efforts: pp. 62-63. In all, it was about a half-hour conversation; the enthusiastic service and insight granted us that day back in 2003 continuing to guide my understanding of the battle, still ringing close despite the years.

Chatham itself is located north-central of the many mile-long Stafford Heights. Along this ridge, Union artillery lined up as infantry support. O’Reilly’s pre-battle estimate was 147 guns, the number increasing to over 180 once the battle was joined. Putting the ranger’s knowledge into context, a quick calculation of the standard 14’ between guns (and giving an additional 6’ for each gun in figuring most batteries were not on top of one another), the Union artillery easily stretched many miles to north and mostly south of the house grounds. A modern artillerist might return a yawn. But in those days that was a brand of firepower that had rarely, if ever been equaled in all of history; which makes the fact that it was largely ineffectual in support of both the upper and middle crossings and the battle itself a hard fact to process. But then, so much about The Battle of Fredericksburg follows suit. It is next-to-impossible for the modern mind to comprehend why things went down as they did here in December 1862.

* * *

In raw numbers, Fredericksburg would be the largest battle fought during the Civil War. The Army of the Potomac, as mentioned, assembled up to 118,000 men; The Army of Northern Virginia over 78,000. Neither army would again field so many soldiers, if only due to the grisly grinding attrition that would characterize this war. Fought on the cusp of an industrialized era gaining full-steam where military tactics had been outpaced by the “technology of death”—the rifled musket with an effective range triple the distance of its smoothbore predecessors proving the main culprit—this war would tax the flesh-and-blood that did the fighting and dying on both sides. Manpower, and the inability of the Confederacy to keep pace with the seemingly infinite waves of bluecoat recruits, would eventually overwhelm its ability to fight on. But aside from a stunning victory at Chancellorsville (still five months off and correctly titled “Lee’s masterpiece”), this Southern army would never manufacture more confidence or expectation of eventual victory than here at Fredericksburg.

Robert E. Lee, a master at reading opponents, positioned the brigade of Mississippi firebrand William Barksdale in the town to contest crossings he knew were coming. The creaking rumble of wagons ferrying the pontoons to the riverbanks, the barking of orders and the work of Union engineers could clearly be heard in the first dim hours of December 11. This would be the day the Confederates, as confident in their position and leaders as the Union army was disillusioned, had hoped for. The Yanks were coming to them.

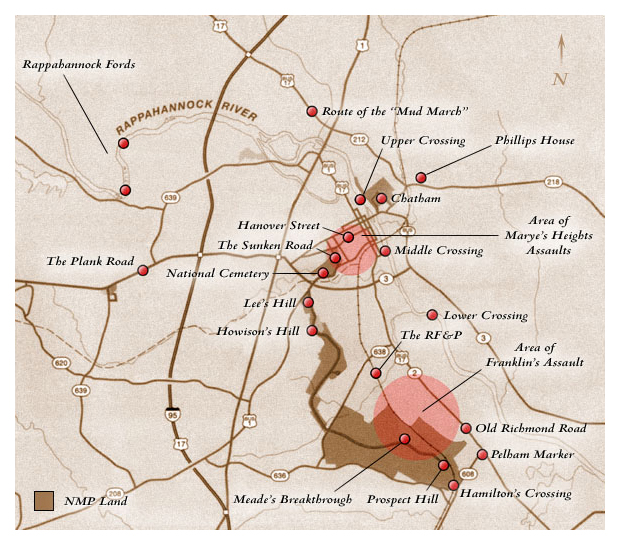

The upper crossing was two pontoon bridges that would land in front of Hawke Street. The middle, a single bridge, would land just south of the town proper at the town’s wharves, now “City Dock” (a popular place for anglers in all of my visits). The lower, three bridges, would span a riverbend a few miles south of the wharves. Sumner’s Grand Division was chosen to cross the upper and middle bridges first, with Hooker’s in support. Franklin would put his men over the lower bridges, these lower crossings not encountering the stiff resistance Barksdale was to train on U.S. engineers from within Fredericksburg’s residential and business district.

The grey streaks of dawn soon lit the shadows of men moving hastily in the fog as the bridges inched their way across the river. Barksdale (on orders) ordered his men not to fire until the engineers were fully committed and daylight provided clear targets. The engineers continued uncontested until the fog began to lift. With the upper and middle bridges about halfway across the river Barksdale’s riflemen opened up, dropping the skilled—and irreplaceable—engineers with deadly proficiency. Those not hit by these initial volleys sprinted back for the east shore. Efforts to resume work under fire was understandably pursued with little inspiration. By 9 a.m., Union chiefs were forced to order artillery to pound the town and force out the resourceful Confederate marksmen firing from the cover of alleys, upstairs windows and stonewalls. The bombardment thundered across the valley and blasted the the historic downtown, but did little good. As soon as the U.S. guns began to cool, the engineers ran back to work only to drop dead and wounded into the river from the resumed fire of Barksdale’s men. The artillery repeatedly attempted to silence this single C.S. brigade, which by that time was holding the core of Burnside’s massive army at bay. Each time the results were the same. A soldier in Zook’s brigade caustically noted: “Thursday was spent in wasting ammunition from about 100 guns.”5 It all had Burnside fuming. The U.S. brass realized they would need an alternate method to clearing out the sharpshooting Southrons.

By early afternoon, the lower crossing, whose construction was the last to get underway, was across the Rappahannock—artillery in the southern sector having cleared the bridgehead effectively. But the failure of the Union artillery to clear the town itself forced the first amphibious landing under fire in American military history (as noted by O’Reilly). It would also lead to the first of very few instances of urban warfare to be conducted during the war. With the pre-winter day wasting away, Burnside reluctantly instructed four regiments—two at each city crossing—to make their way across the river in pontoon boats and silence the riflemen then killing his engineers. The Southerners would contest every inch.

* * *

Crossing back over the river via the old stonebridge at Williams Street and navigating the one-way streets of downtown leads to the upper crossing marker at Sophia and Hawke Streets. From the shelter of houses along Sophia and Caroline, running successively and in parallel with the river, Barksdale’s brigade would accomplish their mission, as put in the Time-Life volume: “superbly.” From there, the tour loops back down Princess Anne Street, west of Caroline, and runs south through the thriving heart of Fredericksburg. This eventually leads to the marker noting the middle crossing at City Docks. Moving through the town itself provides proof-of-concept for maintaining a unique centre for business / culture in contrast to the scorched-Earth trend to line avenues with franchised restaurants and pre-fab shopping complexes that provide no indication of a locale’s unique character—commerce that by-design measures “economic health” via metrics detached from local concerns. Our collective heritage has been rewarded in a big way with the continued preservation and local commerce of this old river town.

* * *

Artillery pummeled the town in the moments before the amphibious assaults were launched. The venture proved risky, even uncertain at the upper crossing site. The 7th Michigan and 19th Massachusetts, with the 20th Massachusetts in support, were frantically rowed across an eighth-of-a-mile of open river. They took a number of casualties while crossing and hit the opposite bank running. A firefight erupted. The concealed Mississippians along Sophia Street punished the exposed assault and then went on the offensive, threatening to hurl the Union troops back into the river. Taking heavy casualties, the crossing was eventually secured, the riverfront cleared of Confederate threats and a bridgehead established. U.S. engineers rushed to complete the crossing while their infantry continued to push back Barksdale’s stubborn, often invisible line street-by-bloody-street. William Davis of the 13th Mississippi wrote: “We killed lots of them in backyards.”6 The 20th Massachusetts would count 97 casualties in a span of only 50 yards by day’s end. Captain Macy of the 20th wrote: “we could see no one and were simply murdered.”7 Two New York regiments met only minor resistance at the middle crossing site, establishing a bridgehead with light difficulty by comparison to the upper crossing. Engineers at both sites had been granted as much safety as they would have in finishing the task, all three crossings fully complete by late-afternoon. Within the town proper, an intense, often confusing, back-and forth battle continued on into the night, Caroline Street serving roughly as the front line. Barksdale’s men continued to extend U.S. casualty lists, threatening more than once to overrun their loose hold on the riverbank. But with four U.S. corps in position to cross and having already fulfilled their mission “superbly,” Barksdale’s men slowly fell back towards the outskirts of town. Aside from skirmishers, they vacated completely under nightfall—dispersing along the bristling C.S. defense within the hills immediately west of town. Burnside had finally entered Fredericksburg. But Lee and the lean hard soldiers from Mississippi had made the U.S. chief pay for it in time and lives.

December 12, 1862, would pass equal parts active, inactive and infamous. Starting in the early frigid hours, Sumner’s men began to cross. By daybreak they were packing into the town. Bridges and roads leading to and from the town, it was said, resembled long blue ribbons. With daylight, the city crossings also provided Confederate artillery an opportunity to test its ranges, a “scrimmage” before the big show. The C.S. gunners lit into the crossing troops with calculated and unnerving effect. Having had over three weeks to prepare emplacements and coordinate fields-of-fire, Colonel Edward P. Alexander, a youthful artillery commander in Longstreet’s I C.S. Corps, would ease the mind of his chief prior to the battle the following day, stating: “General, we cover that ground now so well that we will comb it as with a fine-tooth comb. A chicken could not live on that field when we open on it.”8 Though their ranges proved more unpredictable on the 12th, Alexander’s guns created considerable havoc among the troops of Sumner and Hooker. A U.S. soldier later wrote, “life was cheap that day.”9

Once across, shelter within the town was easy to find and the Union troops settled in for the wait. Boredom mixed with the fuel of general resentment as the day wore on, leading to what was noted in the Time-Life volume as: “one of the War’s more discreditable enterprises.” Beginning in the afternoon, the idle occupying force began to ransack homes. Starting as a hunt for provisions, the search and seizure of “conquered Rebel property” grew to encompass anything the soldiers could carry off. Commanding officers turned their backs as it grew to outright pillaging, many officers participating themselves. Liquor threw fuel on the fire. The whole scene took on a “bacchanal atmosphere,”10 petty thievery turning into “an orgy of destruction.”11 Mirrors, furniture, doors and windows were smashed. Portraits in parlors were stabbed and slashed with swords as desks, chairs and sofas were moved into the streets for more comfortable quarters. Resident heirlooms would be stolen and sent back North as whole libraries were torn from shelves and thrown onto bonfires. Nearly all residents had vacated the town once the two armies had showed, leaving behind most everything. And on the 12th it was all up for grabs. Soldiers paraded around in the residents’ finest clothes and hats. Many dressed up in women’s “undergarments.” Nothing was spared and few soldiers did not partake in this: the first sacking of an American city since the nation’s capitol during the War of 1812. Lt. Josiah Favill of the 57th NY later wrote: “Some carried pictures; one man had a fine stuffed alligator, and most of them had something. It was curious to observe these men upon the eve of a tremendous battle rid themselves of all anxiety by plunging into this boisterous sport.”12 The modern equivalent of the drunken Animal House frat-party would not hold a candle to the destructive mess that was made of Fredericksburg by Sumner’s men. This “sacking” came to seem like an instinctual reaction, a final night of base youthful carelessness before death did its work—a fact each-and every one of them had to be aware was close. What tomorrow would bring was sober enough. And so did the abysmal havoc continue into the thin hours of December 13, 1862.