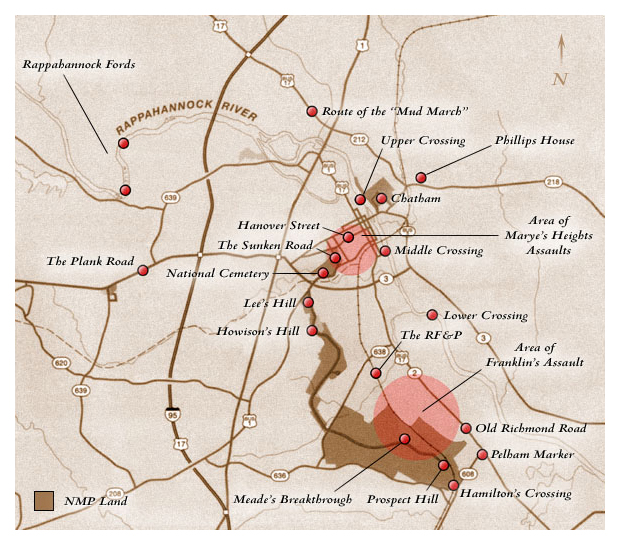

Lee Drive runs north from the southern portion of the National Military Park through a finger of land connecting the divergent north and south fronts. This comes to seem metaphorical, in that two almost entirely separate battles took place at Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862. The assault of Franklin’s Grand Division and the even larger one on Marye’s Heights began at roughly the same time; but neither was in conjunction or provided any lasting support for the other. Both were fought over very different topography, under dissimilar offensive / defensive circumstances, and with inconsistent results—the fight to the south more or less a draw, while the fight to the north was anything but. Of course, taken as a whole the results would prove devastating to The U.S. Army of the Potomac.

Lee Drive follows the route of the C.S. Military Road north towards the town, the preserved tracts here often little more than roadside easements. Aside from artillery, this section of the C.S. line was held in reserve (Hood’s and Pickett’s divisions of Longstreet’s I Corps). Howison’s Hill is the next stop. At 200 feet you can sense the commanding position this hill provided in matching the Union batteries atop Stafford Heights and the murderous cross-fire it could pour down on any assault of Marye’s Heights. The Confederate preparations had been so complete that they’d even had time to haul up a number of big siege guns from Richmond and place them within the Fredericksburg defenses. One was placed on Howison behind a crescent-shaped emplacement that is still well preserved. The next stop is Lee’s Hill, what had been the highest point along the C.S. line and a natural place for the commander’s HQ. It is a short steep walk up a forested rise. Prior to the battle, C.S. Pioneers—the equivalent of the Confederate engineering corps (but for that its main muscle was off-duty infantry)—cleared all of the timber from these slopes to provide a wide-open field-of-fire for their artillery. In doing so, it provided Lee with an unobstructed view for miles in every direction. An informative marker in the shelter on Lee’s Hill details the Pioneers’ role here. By today’s standards their work seems primitive. But then, the ability to forget history for just a moment and venture back through the reality of life in the 1860s is an essential tool in getting closer to understanding our Civil War.

A right off of Lee Drive onto Lafayette Boulevard runs a short leg up to the Visitor’s Center and “Sunken Road” before Marye’s Heights. This is the only NMP unit within the actual town and is far-and-away the most popular destination point. It is the sector for which the battle is most infamously known … On Burnside’s orders, Sumner had moved his troops into position for the assault. Though Burnside had pinned hopes on Franklin’s success, he also sought to break through the Confederate defenses nearest the town regardless of the fight to the south. Again, puncturing Lee’s defenses at any point would likely ripple through the whole C.S. line and open a route south towards Richmond. But this line of defense west of town was unlike anything Meade or Gibbons’ men would encounter. 600 yards beyond Fredericksburg rose Marye’s Heights. It does not carry daunting height; but it is elevated enough to allow complete command of what was in 1862 mainly open fields before it. Longstreet’s artillery had already shown Sumner’s Grand Division what it was capable of during the river crossings. Now those same troops would be heading directly into its teeth. And the brass barrels atop the Heights, which had been lobbing shells into the town since 10 a.m., were in command of every step in between the town and the rise. Add to this formidable line of artillery as strong an infantry position as one could have asked for in that war: a road that ran along the base of the Heights. As was common of the day, years of wagon traffic had eroded the lane to where it was well below ground-level—this stretch running roughly four to five feet deep. Further, the Sunken Road was bounded to the east by a thick stonewall. Facing town, it had been reinforced so that it would not topple. The fiery states’ rights activist, Thomas Cobb, and his Georgian brigade were now positioned in that Sunken Road, having dug the roadside even deeper and throwing additional earth as reinforcement to the opposite side of the stonewall. As noted in the Time-Life volume, Rebels Resurgent: “it was a nearly perfect defensive position.” 19 Against this—the very core of Lee’s line—Burnside would hurl a significant portion of The Army of the Potomac. And so did the grand tragedy come off.

* * *

As mentioned, though documented here in succession Franklin’s Grand Division assault and the assaults on Marye’s Heights commenced at roughly the same time: 11 a.m. Hanover Street runs the same route today that it did in 1862. This would be one of the main arteries for the Union attack. Again, the area over which the attack occurred was mostly clear; but it contained numerous obstacles that would interfere with the advancing formations. Depending on the route of attack, Union troops would have to cross a deep overflow canal ditch (now Kenmore Avenue), an unfinished railroad cut and the outbuildings and fences of the few residences in the area (these also providing what little cover there was to be had). Add to all of this, the attacking columns would have to navigate a large running fence that ringed a fairgrounds spread across the entire assault route … In whole, the area was an oblong trapezoid—its modern boundaries consisting of: the Sunken Road on the west, Hanover Street to north, Kenmore Avenue to east / northeast, and the RF&P on the south heading away to the southwest. Inside what is today a commercial and residential zone about a quarter-mile square, Sumner & Hooker’s Grand Divisions would absorb over 7,000 casualties in a single horrific afternoon.

The U.S. II Corps division of William H. French was given ‘the honor’ of leading the initial assault. The signal honor of lining up in the front ranks of French’s three brigades was awarded to Kimball’s brigade. Marching out Princess Anne Street from what was most likely a very comfortable bivouac—given the pillage of the previous night—Kimball’s men turned right on Hanover and marched west from town. The Washington Artillery, a crack artillery outfit from New Orleans (a memorial in their honor rests in the heart of Jackson Square), was positioned on Marye’s Heights along either side of the mansion. As soon as Kimball’s advance was clear, the Louisianans opened up. Their shells tore into Kimball’s men, who were now confronted with improvising crossings at the canal ditch under intense fire. In single file lines over hastily thrown boards, or splashing through the frigid waist-deep water, they pushed across taking gruesome casualties. Shells tore heads off bodies. Torsos were ripped through by direct hits that showered those behind in a repellent spray of blood, tissue and bone. A soldier in Kimball’s 14th Indiana recalled: “it seemed we were moving in the crater of a volcano.” 20 The brigade regrouped in the fields past the ditch and made their push for the stonewall … This area between Hanover and Lafayette now consists entirely of neat residential blocks. At the time of the battle, one house stood out as most prominent in the area of the fairgrounds: the Stratton House. It still stands, if now blending into the surrounding neighborhood. No vestige of the fairgrounds or open fields remain. In 1862, the Stratton House was the last cover before the Confederate defensive line boiling behind the stonewall in the Sunken Road.

Busting through the fences pinched, split and degraded organization amongst Kimball’s four-regiment front. But this was minor compared to what Cobb’s anxious, yet patient riflemen were set to unleash. At about 200 yards, the Georgians in the Sunken Road let loose. Their fusillade was devastating. Using terminology common to a nineteenth-century and still largely agrarian nation, the front ranks were cut down “in windrows.” The supporting ranks were exposed to the same. Though some ventured beyond that point, Kimball’s assault as a whole made it only as far as the Stratton House at the fairgrounds’ halfway point. Private William Kepler, who was one of those few advancing further out as a skirmisher, wrote: “Wounded men fall upon wounded; the dead upon the mangled; the baptism of fire adds more wounds and brings even death to helpless ones; as we look back the field seems covered with mortals in agony.” 21 One-quarter of the brigade, including Kimball himself, was shot down in less than half an hour; and this was only the crest of the first wave of seven division-strength assaults to be sent forward. Around noon, French ordered Andrew’s and Palmer’s brigades forward. They were met with the same ferocious killing power. Cobb’s Georgians had been reinforced with additional troops from North Carolina. The Confederates now stood several ranks deep in the Sunken Road, a revolving firing-line at the stonewall. A continuous murderous sheet of lead poured out over the attackers. A Private Cory in Andrews’s advance: “[we were] almost blown off our feet.” 22 French’s assault was quickly bled to a halt. The survivors slunk into a swale that ran across the fairgrounds before the Stratton House. (What is left of this depression is still visible in front of the route of today’s Littlepage Road.) U.S. artillery was called in to try and soften the C.S. positions. But it was ineffectual, outside of a piece of errant shrapnel bounding up and slicing through Thomas Cobb’s thigh and leg. Severing the femoral artery, it quickly proved a mortal wound … The U.S. II Corps division of Winfield Scott Hancock was ordered to advance.

* * *

You can sense a brutal pattern in the making from the very start of researching the assault on Marye’s Heights. Out walking along the Sunken Road, you feel it viscerally. It is the sense of tragic history mentioned in the intro to this piece. All this time later, it still hangs as a pall. This is truly “shadowed” ground … When I revisit Fredericksburg and walk this section of the park, I am reminded of how on the 2003 tour, Dad & I came back to an earlier discussion on the sense of duty that came to, and was expected of the Civil War’s rank-and-file as we walked the length of the preserved Sunken Road: How these men often made their “peace” and then marched out to certain death. I also recall a hard crystallization of this moment in a passage from Charles Frazier’s fictional work, Cold Mountain (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1997)—how his character, Inman, accurate as a North Carolinian behind the stonewall, came to hate the Yanks not so much for their being the enemy, but more for their “clodpated determination to die.” The Sunken Road, now at peace and lined of old locusts, is a stark walk.

* * *

Winfield Scott Hancock was a regular army officer in the mold of George Meade. He was hard-driving, expected much and usually received it. He would cement his reputation defending “The Angle” against Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg the following summer. But at Fredericksburg, his men were on the attack; and their task was more than Robert E. Lee would ask of his men the following summer. Hancock’s three brigades marched out and assembled where the town limits then traipsed off south of the canal ditch. The brigades of Colonel Samuel Zook, Meagher (the storied “Irish Brigade”), and Caldwell were lined up and sent forward in that order. With the Confederate artillery already hammering away, Zook’s men went forward and straight into the living truth of his grim assessment from a few days earlier. The fairgrounds fencing would prove to be an enemy of the Union assaults all afternoon, breaking them into piecemeal bands that were then ground down by the impregnable hail of bullets and canister exploding with murderous resolve from the C.S. line. So did the Southern rifles behind the stonewall erupt into the face of Zook’s disorganized men, beating them down in the fairgrounds. A North Carolinian would later write: “They were brave men and it looked like a pity to kill them.” 23 But kill them they did, by the score. As Frank O’Reilly writes: “The Confederates mauled the silently approaching mass of bluecoats.” 24

Probably the most documented charge of this slaughter was that of the legendary “Irish Brigade.” In the impassioned moments before they stepped off, commander Thomas Meagher handed out green sprigs of boxwood to his troops as a reminder of their heritage, empowering them with the blessings of their God, their cause, and the expectation to do their duty. With the green sprigs tucked proudly in the bands of their kepis, Meagher’s men marched forward and were mowed down, a regiment at a time. An officer would later claim of his fellow Irishmen: “they were not there to fight—only to die.” 25 There are numerous claims on the unit that drove on closest to the stonewall, a gruesome honor and headstone-epitaph all in one. Inside the adrenaline, cacophony and mayhem on the field that day it seems impossible to know for sure. But is said that the “Irish Brigade” did advance the furthest. No column drove any closer than 40 yards of the stonewall. Not a single Union soldier made it to the C.S. line … Hancock’s final brigade was Caldwell’s, whose men followed directly behind Meagher’s. Their results were no different. The 5th New Hampshire advanced furthest before they too were blown back into the swelling ranks of those still living and huddling in the swale, behind torn-down fencing, or inside the Stratton House itself. Two divisions had been destroyed without making a dent in the Confederate line of Georgians, Carolinians and Louisianans posted to defend Marye’s Heights. Hancock’s division suffered over 2,000 casualties alone, absorbing one of the highest divisional casualty rates (in terms of percentage of those engaged) of any battle of the war. Furious and heartbroken, Darius Couch, commander of the U.S. II Corps, was overheard yelling: “See how our men, our poor boys are falling!” 26 He would later note of the slaughter before the Sunken Road: “the men were asked to conquer an impossibility.” 27 But unlike the misinterpretation of Franklin, Burnside’s orders on this front were explicit: continue the attacks. And so, Couch ordered his final division forward.

* * *

Continuing down the Sunken Road, you pass by the small granite block in memory of Thomas Cobb, marking the spot behind the Stephens House where he was struck. The Stephens and Innis House were the only structures incorporated into the Sunken Road line. Both are small farmhouses of the day restored to their original appearance. Martha Stephens was seen during the battle courageously issuing aid to wounded Southerners. The Innis House still bears battle scars, now over 150 years old. At the end of the Sunken Road stands the only original section of the stonewall. The view from behind it is still “sunken,” as it was during the battle. Standing here provides a pit-of-stomach churning view of the strength of this position: It is impregnable. A few hundred feet in front of the stonewall, apartments and homes now stand. It takes some imagination, let’s call it an appalling creativity in attempting to recreate the human destruction that occurred out there. It is an odd thing to know what happened and to also view a society having moved on, the town blending seamlessly—casually—with the park.

* * *

Oliver Otis Howard, commander of Couch’s final U.S. II Corps division, marched his men out of the city around 1:30 p.m. It was about this time to the south that Meade’s assault was punching through Gregg’s brigade and pouring over the C.S. Military Road. But on this northern front—wholly separated as it was from what was occurring to the south—even a glimmer of victory was reserved only for the unrealistic. And as the afternoon wore on, it must have seemed that only Burnside could muster such unrealistic hope—if even he could do so. For the results of these continued assaults were becoming more and more predictable … Howard’s men, once clear of the canal ditch, lined up straddling Hanover Street and moved forward. Continual reinforcements from Ransom’s North Carolinian and Kershaw’s South Carolinian brigades’ had been fed into the C.S. line behind the stonewall. Joseph Kershaw, now in command with the mortal wounding of Cobb, presided over what was likely the strongest infantry position of the war. And his rifles, along with the belching fury of the Washington Artillery from the Heights, leveled the approaching masses of Howard’s men. Both Owen’s and Hall’s brigades of Howard’s division were massacred in short order. Howard’s final brigade moved up in support only, wisely opting against a third push.

As 2 p.m. approached, Union commanders in the field began sending back urgent demands for reinforcements in order to stave off a possible Confederate counterattack. Units of Willcox’s U.S. IX Corps (Sumner’s Grand Division), were ordered over the middle crossing at the city wharves. Sturgis’ division went across first. They marched out past the train depot and were faced west towards the canal ditch. The left flank of the advanced Union line, such as it was: jumbled, prone and bleeding in the swale, lay unsupported and vulnerable. Ferraro’s IX Corps brigade was the first to go forward. They moved out in the area of modern-day Lafayette Boulevard and straight into the maelstrom. Despite a ‘spirited’ advance, they were raked with fire once within range. The Confederates in the Sunken Road had begun to wait on each successive advance, goading each to come closer than the last before they would open up. And when they did, their fire was impenetrable. Nothing could stand it. Ferraro’s men were chewed up like all those before them. They faltered, broken and confused, within the fairgrounds and only managed to join the writhing remnants of those broken before them. A soldier in Ferraro’s advance later recalled of the fairgrounds: “[men] lay weltering in their gore.” 28 The U.S. troops—dangerously exposed, despite the swale—had begun to create breastworks by stacking their own dead comrades. This was as brutal a day as our country’s history has ever known.

Nagle’s brigade of Sturgis’ division followed Ferraro’s men on their left in order to extend the line. Their advance proceeded up the unfinished railroad cut, a westbound spur off of the RF&P. But the advance came under precise C.S. artillery fire within the manmade ravine and was decimated. Survivors came up on the very left of the fairgrounds and charged the ground now occupied by the Visitor’s Center. A claim is made that it was the 9th New Hampshire, not a portion of the Irish Brigade, who advanced further than any other unit that day in storming the stonewall. Regardless, the 9th New Hampshire and the rest of Nagle’s assaulting columns were ground down and thrown back. Another attack had been defeated … Burnside did not hesitate in calling up Hooker’s Grand Division.

* * *

Walking up Mercer through the break it makes in the stonewall brings you into the modern neighborhood that now stands where the fairgrounds and open fields of 1862 had been. A Civil War-era roadbed, Mercer was an attack avenue for the U.S. II Corps on December 13, 1862. The Stratton House stands at its corner with Littlepage Road. Littlepage runs in parallel with the stonewall and marks the farthest point that the Union attack would progress as a whole. It is a full 500 feet from the Sunken Road … Normally, I would fume over development of “core battlefield land,” especially in contemporary times; and there is no more core battlefield land in the country than this block in west Fredericksburg. And yet, when I do walk this neighborhood I have more than once thought that in this instance perhaps allowing a quiet tidy neighborhood to build up and over “core” land was maybe not such a bad idea: Honor the fallen elsewhere (as they are done in a solemn moving way within the park’s National Cemetery) and allow time to erase the physical vestige of an inexcusable tragedy. I have never felt that way about even an acre of Civil War battlefield anywhere else —— that it was just better left forgotten.

* * *

It was mid-afternoon on that Saturday in December, 1862. Meade and Gibbon’s men had been driven back, as had the courageous, if reckless counterattack by Atkinson’s Georgians. A minor clash developed between the north and south fronts along “Deep Run,” a stream that split the two fronts. A Union reconnaissance unit was driven back in this area by the Confederate troops they encountered. The Confederates had come out in force, perhaps sensing the tide of the battle was on their side; but they were soon halted in turn by a U.S. attachment. This stabilized the tenuous centre of each army’s lines. The only heavy fighting for the remainder of the day would occur in front of the Sunken Road.

Center Grand Division commander, Joseph Hooker, saw for himself what was occurring in front of the stonewall; while, Burnside, whose HQ was located in the Phillips House on the opposite bank of the Rappahannock, was well removed from the futile bloodshed. Hooker would boil over into open and bitter insubordination following the battle, his eyes then fixed on Burnside’s command. But on this day, he reluctantly ordered forward the fifth assault of the day: Griffin’s division of Butterfield’s U.S. V Corps. The time was 3:30 p.m. Griffin’s first brigade—Barnes’—moved up from where Lafayette and Kenmore now converge west of the train depot. Griffin personally led forward the 18th Massachusetts. But examples of manly courage meant little before the grim reality of storming the stonewall on that afternoon. Barnes’ men were blown away before they could even gain momentum. The brigade was stunned to a halt on the west side of the fairgrounds. Sweitzer’s and then Carroll’s (U.S. III Corps) brigades went forward successively in their wake. Both were beaten into a bloody mass. A Pennsylvanian in Carroll’s brigade said: “It looks to me as if we were going over there to be murdered.” 29 Griffin’s final brigade—Stocktons’—moved up in support only, taking a bloody beating as they did. The soon-to-be legendary 20th Maine advanced with the rest of Stockton’s brigade. It was their first test under fire, a gauntlet that made even the hardened veterans cringe. And as had been true of the entire day—along both Union fronts—these four brigades had gone forward one-following-the-other in uncoordinated and unsupported advances. They were summarily ground up one-after-another … Hooker called up Humphrey’s V Corps division.

Having entered Fredericksburg via the upper crossings, Humphreys’ division marched out and up Hanover Street, lining up for their turn against the almost jubilant and certainly confident Confederates behind the stonewall. At a little past 4 p.m., Allabach’s brigade moved forward as the vanguard. Tyler’s brigade was marched out on their right, then moved in behind them. Both advanced in direct line of the Washington Artillery’s guns, which opened up and tore up this sixth major assault of the day. Humphreys courageously and recklessly led the attack, which included many “green” troops (including the general himself). The attack stalled under intense fire from the Sunken Road position. Yet to Humphreys and others it suddenly seemed as if the Confederate artillery atop the Heights was pulling out. The Louisianans had depleted their ammunition; but far from retreating, they were being replaced by fresh reserves. The mistake in judgment was tallied in more Union lives. Humphreys ordered his men to fix bayonets and charge the stonewall, personally leading the attack. Survivors in the scattered advanced line then hugging the ground behind breastworks of dead comrades, reached up and grabbed at the feet and legs of the troops as they went forward—pleading with them to give it up, that is was suicidal. The charge made it to within 50 yards of the stonewall before the waiting Confederate rifles, by this point four ranks deep, erupted in their face. The front line of Humphreys’ charge melted in a gruesome bloody heap. A second push forward was beaten down likewise. The broken remnants were sent reeling. Having watched the massacre, a furious Hooker stood down any further assaults by his men and even pulled the survivors of Humphreys division out of the advanced line—which by then stretched over a quarter-of-a-mile from the railroad cut, across the fairgrounds, Stratton property and Sisson store (a grocer whose lot bordered Hanover Street), and extending north of Hanover towards Williams Street (modern-day route 3). Hooker would later state, acidly, that he had “lost as many men as his orders required.” 30

Yet with dusk turning on night, a seventh futile assault was already underway. Getty’s U.S. IX Corps division was moved up from the middle crossing site and forward along the RF&P. The advance became disoriented in a bog just north of the depot and proceeded to cross the railroad cut in disarray. With Rush Hawkin’s brigade in the van (the same officer who’d told Burnside the attack “will be the greatest slaughter of the war”), the assault found some semblance on the very left flank of the advanced line. They rushed forward. In the fading grey twilight, Hawkin’s men advanced undetected near the ground now occupied by the Visitor’s Center. But their enthusiasm gave them away, as they yelled in charging the stonewall. The surprised Carolinians defending this stretch of the stonewall quickly leveled their muskets and lit into this final attack. Despite closing to within 40 yards, Getty’s troops were torn apart. Sheets of rifled flame lit up the dusk, blowing away the lead elements of the charge. Again, the blue columns were thrown back … And with that, the assaults on Marye’s Heights came to a merciful end. The frigid night would bring misery.

Epilogue .

Before the original stretch of stonewall stands a stirring bronze statue in honor of Sergeant Richard Kirkland, who was positioned behind the stonewall with the 2nd South Carolina. On December 14th, after enduring two days of having to listen to the immobile Union wounded crying for water, Kirkland found himself no longer able to stand by and do nothing. Receiving permission—but no guarantee for his safety—he gathered as many canteens as he could carry and entered the field before the stonewall. Since the battle had ended, sharpshooters on both sides had been targeting anyone who dared show themselves. Kirkland was not deterred. Rifles opened up on him. But when he knelt down to issue water to a wounded Union soldier, and then another—often covering the wounded men with their overcoats before moving onto the next and repeating the process—his mission of mercy became clear and the firing stopped. This act prompted others, from both sides, to do likewise. Those who witnessed Richard Kirkland’s brave compassion would call him: “The Angel of Marye’s Heights” … Kirkland was killed the following September at Chickamauga.

A kind of mental exhaustion can settle in while touring the Sunken Road. The emotion of the place seems visible, almost tangible; at the very least, it is something that works on you. This is a sense only reinforced by the National Cemetery, which rests on a knoll above and behind the reconstructed stonewall. It is a fitting place to end a tour of the Fredericksburg NMP, filled as it is by those who had died in the desperate drives on the stonewall and in the field hospitals during the days that followed. As you enter the cemetery, a sign notes a few facts: the plot of 12 acres was bought in 1865 for $3001.25. Over 15,000 individuals are interred there and only 15% were ever identified. In 2003, I jotted the following in a travel journal: “The National Cemetery … a great little walk amongst the maples, the cedars, the holly—and the dead.”

* * *

All through the night of the 13th, and the following day and night of the 14th, the advanced Union line—the dead and living remnants of seven divisions—was held in place, enduring scant protection as they huddled in the swale’s slight depression. Any movement during daylight was likely to bring a sharpshooter’s minié ball. And being December, night-time temperatures sank. The cold clear nights brought many Confederates over the wall (and out in front of Jackson’s lines to the south, as well) to strip the dead or invalid Yanks then carpeting the ground of their government-issue boots, pants, shirts, overcoats—everything. Unscrupulous pillagers from both sides (and the armies were full of them) robbed the same dead and invalid of all valuables that might be of worth. Add in the ceaseless cries of the wounded for water, care and mothers in far off homes, and the scene on the frigid morning of December 14, 1862, can hardly be imagined: hundreds of frozen corpses stripped of every scrap of clothing and possession. Only the protests of those still alive and pinned down seemed to prevent every Union casualty in front of the stonewall from the same fate … And yet, despite clear evidence of the catastrophe that had unfolded before the Sunken Road, Burnside, remarkably, had to be talked out of renewing the assaults—at one point, even insisting that he personally lead the charge. Many of those present would later speculate that the commander’s sole wish was to have his own lifeless body strewn among the thick carpet of dead. Mercifully, Burnside was talked of so foolish an order—the Union dead continuing to lay naked, the Union living still among them.

Lee, having further reinforced and strengthened both the northern and southern sectors of his line, attempted to bait Union commanders into attacking on the afternoon of December 14th. But the Confederate jockeying of forces and ruse of a threat went wholly unnoticed amongst the U.S. brass: beaten, despondent, and almost uncaring … The long day passed terribly for the Union. Word had made its way to the capital and Lincoln, the President summarizing the shock that so massive a defeat would have on northern morale, stating: “If there is a worse place than hell, I am in it” 31 … And yet by contrast, the Southern ranks, many now sporting warm blue overcoats and new boots (both rare commodities for any Confederate army), this “splendid victory” 32 had to make the pre-winter nights pass a bit easier; add to it, a natural phenomenon that was read as heaven having willed a Southern victory. That night, the northern lights lit up the night sky. This was a very rare phenomenon so far south, a celestial show that was seen as nothing less than confirmation of victory being heaven sent. A Confederate artillerist would note: “the heavens were hanging out banners and streamers and setting off fireworks in honor of our victory” 33 … It should be noted that both sides prayed to the same, or at least a very similar God, sought the gracious will of heavenly intervention and the merciful blessing of splendid victories for their respective causes. However, in the post-battle fog that hung over The U.S. Army of the Potomac, it seemed to many in its ranks that they’d been abandoned—on the temporal and spiritual plane. Morale, already low prior to battle, sank even lower. Desertions would plague the army’s rolls well into 1863.

On December 15th, the first formal truce was called since the end of the fighting to collect the wounded still alive. That night, the wooden planks of the three river crossing sites were muffled with hay and dirt and the Union army was withdrawn from Fredericksburg and the west side of the Rappahannock to fields east of the river. Engineers pulled up the crossings behind the withdrawal and the Union was left to plumb the depths of the tragedy. The northern forces had suffered almost 13,000 casualties. Nearly two-thirds of those men fell before the stonewall. The Army of Northern Virginia had suffered just over 5,000, only one-fifth of that total in defending Marye’s Heights. It was as lopsided an outcome as the war would produce.

As he had watched over the appalling destruction of human life on December 13th, Robert E. Lee—a man who understood battlefield courage, but could also articulate its real price—was said to state: “It is well war is so terrible, lest we grow too fond of it.” Such a statement says an awful lot about the era in which this war was fought, one that contained hard-boiled cynics enough, but more often rocked about within simple romantic tides. Common enough views drove a blind faith that could be awarded with a shocking and fated ease in the face of criminal failures of leadership, soldiers doing their duty just as often looking as if they had a “clodpated determination to die” … And yet perhaps because of such resolve, so many men and women of the time could recover in the face of so devastating a loss. For it would become evident that this Union army in particular contained grit and fiber enough to absorb such a disaster as Fredericksburg and continue to fight the fight. And this—we now know—in the face of six more months of continual mishaps and one more titanic defeat.

To his credit, Burnside set right to mounting another flanking maneuver that, with celerity, might have been able to push beyond Lee’s flank and force The Army of Northern Virginia from its impregnable positions. But the plan lost its wind in the political wrangling between the executive branch and Army of the Potomac leadership during those final weeks of 1862. The fallout from Fredericksburg overshadowed all tactical discussion. Burnside’s plan was delayed by three weeks and Mother Nature took over from there. On January 20, 1863, Burnside set his army in motion west along the north banks of the Rappahannock. The aim was to quickly secure and cross the lightly guarded fords in Lee’s rear, and outflank him. The 20th began as a beautiful winter day; but by evening, clouds forewarned trouble. During the night, a cold rain and sleet began to fall. It would rain for two solid days. Union soldiers claimed that the bottom fell out of the roads, which were churned into long ribbons of boot and wheel-sucking muck. The infamous “march” stalled in the mud. Mules by the hundreds were so blown by the labor of transporting supply trains through knee-deep mud that the only humane thing to do was cut them loose and shoot the poor dying animals. Confederate pickets watching the darkly comic “Mud March” from the opposite bank could only heap further humiliation on the exhausted muck-caked Union troops. They painted a message atop a barn roof clearly visible from the north bank that read: “Burnside’s army stuck in the mud.”

The bluecoats, now even more demoralized, trickled back into their winter encampments at Falmouth across the Rappahannock from Fredericksburg. Burnside was summarily relieved in favor of his virulent rival, “Fighting” Joe Hooker. One disastrous tenure had been terminated for another, the latter to meet his fate that May at a rural crossroads ten miles down the Plank Road called Chancellorsville.

Bibliography:

O’Reilly, Francis Augustín. The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003.

The Civil War: Rebels Resurgent; Fredericksburg to Chancellorsville. Alexandria, Virginia: Time Life Books, Inc., 1985.

Voices of the Civil War: Fredericksburg. Alexandria, Virginia: Time Life Books, Inc., 1997.

Foote, Shelby. The Civil War, A Narrative (Vol. 2: Fredericksburg to Meridian). New York: Vintage Books, 1986. (Originally published by Random House, 1963)

Catton, Bruce. The Army of the Potomac (Vol. 1: Mr. Lincoln’s Army / Vol. 2: Glory Road). New York: Anchor Books Doubleday, 1953.

Footnotes:

As true of our Almanack pieces, this was intended less as a research tool and more as a general study. Still, I felt the need to list footnotes on direct quotes—most taken from soldiers’ letters, written recollections, etc—in order to providing a route to vital primary sources.

- Samuel Zook: Voices, Fredericksburg; Time-Life (Alexandria, 1997), p. 31.

- Rush C. Hawkins: Rebels Resurgent; Time-Life (Alexandria, 1985), p.41

- Joseph H. Taylor: Ibid, p.41.

- Wesley Brainerd: The Fredericksburg Campaign (Baton Rouge, 2003), p. 58.

- Soldier in Zook’s brigade: Ibid, p. 68.

- William Davis: Ibid, p. 94.

- George Macy: Ibid, p. 93.

- Rebels Resurgent; Time-Life, p. 73.

- Connecticut soldier: O’Reilly, p. 111.

- O’Reilly, p. 121.

- Ibid, p. 123.

- Josiah Favill: Voices, Fredericksburg; Time-Life, p. 50.

- Maine soldier: O’Reilly, p. 164.

- North Carolina Soldier: Voices, Fredericksburg; Time-Life, p. 68.

- O’Reilly, p. 220.

- O’Reilly, p. 217.

- Soldier in the Pennsylvania Reserves: Ibid, p. 226.

- Jacob Heffelfinger: Voices, Fredericksburg; Time-Life, p. 77.

- Rebels Resurgent; Time-Life, p. 73.

- Soldier in 14th Indiana: O’Reilly, p. 255.

- William Kepler: Voices, Fredericksburg; Time-Life, p. 84.

- Soldier in Andrew’s brigade: O’Reilly, p. 266.

- North Carolina soldier: O’Reilly, p. 304.

- Ibid, p. 305.

- Irish brigade officer: Ibid, p. 316.

- Darius Couch: Ibid, p. 273.

- Darius Couch: Ibid, p. 332.

- Soldier in Ferraro’s brigade: Ibid, p. 340.

- Pennsylvania soldier: Ibid, p. 375.

- Rebels Resurgent; Time-Life, p. 87.

- Ibid, p. 93.

- Description in the Richmond Examiner: Ibid, p. 92.

- O’Reilly, p. 441.